“Yeh Nishtar Park kī majlis-e ʿazā Imam Husain kī university kī aik majlis hai, aik class hai, yeh mukhtalif campus haiṉ jinheiṉ hum imāmbārgāh kehte haiṉ, jinheiṉ hum ʿazākhānah kehte haiṉ, ʿāshūrkhānah kehte haiṉ . . .”

“This majlis-e ʿazā of Nishtar Park is one majlis, one classroom of Husain’s University. What we call an imāmbārgāh, an ʿazākhānah, an ʿāshūrkhānah are different campuses [of Husain’s University] . . .”

On the ninth day of Muḥarram in 2019, addressing a physical crowd of roughly one hundred thousand devotees, and a virtual crowd of many more thousands, Shahenshah Naqvi, Pakistan’s most visible Twelver Shiʿi orator today, theorized the majlis-e ʿazā, Shiʿi gatherings to commemorate their Imams, by foregrounding the epistemic, rather than mourning, dimensions of the gathering (Shahenshah Naqvi 2019).[1] Naqvi offered the signifiers of university, classroom, and campus as analogous to the vernacular terms “imāmbārgāh,” “ʿazākhānah,” and “ʿāshūrkhānah,” each of which references Shiʿi gathering places in South Asia. Naqvi’s equivalence-making was not unprecedented.[2] Indeed, in the course of my fieldwork that summer, I had heard other khat̤ībs (orators) such as Nusrat Bukhari and Kumail Mahdavi, both of whom enjoy large followings in Karachi, utilize the English epithet “Husain’s University” in their orations for purposes similar to Naqvi’s. Husain’s University, this article suggests, is not merely catchy: the title indexes pervasive contemporary Shiʿi attitudes in Karachi toward ritual oratory, khit̤ābat, which is heralded by the devotees as “a method of nurturing, and especially the nurturing of the new generation” (Sadiq 2009, 9); a practice that “[consists of] subjects and subject-matters that influence our actions” (Razmi 2005, 9); and an institution through which “the people of our nation, from a young age, learn much more than people of any other nation” (Z. A. Naqvi 1993, 7). Attention to the epistemic dimensions of Urdu Shiʿi khit̤ābat helps move beyond the restrictive categories of “sermon” and “religious edification” through which existing scholarship has approached the practice (Schubel 1993; Howarth 2005). Indeed, I argue that the very performance of khit̤ābat is intertwined with, and partakes in, important emic debates on the typologies of oratory. I engage textual and ethnographic examples to demonstrate how khit̤ābat is an integral medium through which Shiʿi devotees interact with ideas, persons, and events from Shiʿi memory, even as khit̤ābat itself becomes an object continuously contested over by orators and devotees alike. The case of the Urdu Shiʿi khit̤ābat in contemporary Karachi illustrates the necessity of examining texts and practices that are in constant and consistent conversation with one another.

The invocation of the university as a metaphor for ritual oratorical practice is interesting on many levels. The university draws upon commonplace notions of institutions of specialized learning, with the khat̤ībs invested in positing khit̤ābat as a domain where knowledge is produced and communicated with an eye toward raising the intellectual and professional caliber of the attendees. The university has, in the context of the world that we live in, also become a symbol of progress. Khit̤ābat is often claimed by Shiʿi devotees as a similar symbol and practice, especially relative to what they consider the more rigid forms of Sunni Islam. The university is, at least theoretically, an institution that is accessible and inclusive. Positing the majlis (a commemorative assembly in which the dead are mourned) as a whole as similarly welcoming to all and sundry, regardless of creed and orientation, performs an important rhetorical function of eradicating, or rising above, differences that otherwise mark everyday life (Schubel 1993). Of course, the university has also become, at some level, a necessary institution insofar as it impacts individual economic prospects: the analogy here extends to posit that khit̤ābat, a metonym for the majlis, serves a similar differentiating function when it comes to the eternal life that devotees will live in the world to come.

In this article, I attend to “Husain’s University” through two specific nodes that constitute oratorical networks in contemporary Karachi. First, I discuss the categories through which khit̤ābat as well as khat̤ībs are referenced in local texts and practices. Existing scholarship on South Asian Shiʿism has opted to use the word “ẕākir” (sermonizer) to reference ritual orators (cf. Pinault 1992; Schubel 1993; Bard 2002; Howarth 2005; Hyder 2006; Ruffle 2011; D’Souza 2014). In most of this scholarship, ẕākir derives from its frequent usage among the Shiʿa in Hyderabad, India.[3] Yet a similarity of language (i.e., Urdu) and tradition (i.e., Twelver Shiʿism) across the contexts of Hyderabad, India, and Karachi, Pakistan, does not translate into a similarity of categories of analysis and experience. I draw upon theorizations and practices pervasive in contemporary Karachi to argue that here ẕākir and khat̤īb are not neutral signifiers but participants in active, emic taxonomic debates. Consequently, scholarly usages of these categories to reference Shiʿi practices in Karachi must capture the importance attributed to these titles by Shiʿi devotees as well as indicate the hierarchies that these titles help create, sustain, and reinforce in Shiʿi practice. Second, I examine how khat̤ībs do not simply theorize the genre as epistemic but also engage in scholastic practices that reinforce their rhetoric. To this end, I examine the khat̤ībs’ reflexive considerations of the importance of introducing and engaging in new scholarly research. I also interrogate citational practices that undergird khit̤ābat to show how citations help the khat̤īb demonstrate their command over texts and archives. The privileging of the epistemic dimensions of khit̤ābat, of which the epigraph to this article is just one example, is concomitant with scholastic practices, such as the sharing of original research and the demonstrating of a mastery of various bodies of historical and contemporary scholarly works, that khat̤ībs undertake. I illustrate both of the aforementioned nodes—categories of oratory and the epistemic dimensions of the ritual practice—through an example from my ethnographic fieldwork in Karachi. In this performance of an anecdote revolving around Muhammad and a bee, we evince concrete instances of not just how theological doctrines are presented to the devotees but also how the very presentation of the anecdote itself lays claim to the epistemic authority of the orator. I begin with a brief description of the ritual performance of khit̤ābat.

The ritual performance of khit̤ābat

The ritual lives of Shiʿa devotees revolve around the majlis, commemorative assemblies in which the dead are mourned. These majālis (sing. majlis) range in size from small, immediate-kin-only events to large, public affairs; these events are sponsored by individuals or institutions, or a combination of both. Majālis take place throughout the year, though they rise in frequency and visibility during the Islamic calendar months of Muḥarram and Ṣafar, when the Shiʿa commemorate the martyrdom of Husain at Karbala in 680 ce. For the rest of the year, the majālis stay impressively constant because of their integral role in Shiʿi death rituals. Generally, deceased individuals are commemorated through public and private majālis. The public majālis are generally held on the second or third day of their death (soʾyam), as well as a few weeks later (chihlum).[4] The period between the soʾyam and chihlum is marked by smaller, generally private majālis held in the house of the deceased. After the chihlum, the next major commemoration of the deceased is a death anniversary majlis, the barsī kī majlis, cementing the event in the ritual calendar of the devotees. The largest and the most visible majālis tend to be the death anniversaries of the Shiʿi Imams, especially Husain and his Karbala supporters. There are also significant majālis held for the Prophet Muhammad, his daughter Fatimah al-Zahra, and other important defining events in Shiʿi historical narratives. Majālis for Husain (held on 10 Muḥarram but also on other days such as 20 Ṣafar, to mark his chihlum) and his friends and companions (held in the first nine days of Muḥarram as well as on other days in Muḥarram and Ṣafar) attract the most devotees. Notable crowds are also witnessed at the majālis for the death anniversaries of ʿAli (held from 18–21 Ramaẓān), Hasan (27 Ṣafar), Muhammad (27 Ṣafar), and Fatimah (held between 13 Jumādā al-Awwal and 3 Jumādā al-Sānī).[5]

In addition, there are also fixed weekly majālis at a few places in Karachi—these tend to be more intimate, especially since they attract regular devotees. For instance, Maḥfil-e Shāh-e Khurāsān hosts a majlis every Thursday after maghrib, Imāmbārgāh Bāb ul-ʿIlm has a similar majlis every Sunday, and so forth. A Shiʿa devotee in Karachi juggles a calendar full of religious (dates commemorating Shiʿi historical figures and events) and social (the majlis as a part of extended death rituals) obligations, both pertaining to the majlis. It is common for devotees to attend multiple majālis a week, thus driving home the ubiquity of the practice. I should also note the significant regional variations of the Shiʿi majlis in Pakistan, and South Asia more broadly (cf. Pinault 1992; Hyder 2006). Importantly, these differences in the form and content of the majlis across South Asia should not be read as iterations of some original practice: what is crucial is to take the proliferation of the majlis as indicative of the centrality of these gatherings in the daily lives of Shiʿa devotees.

The Karachi majlis generally consists of fixed segments performed sequentially.[6] These include the recitation of ḥadīs̱-e kisāʾ,[7] soz and/or mars̱iyah,[8] salām,[9] khit̤ābat,[10] nauḥah,[11] and ziyārat.[12] These segments, especially ḥadīs̱-e kisāʾ, soz, and salām, are preludes to khit̤ābat, demonstrating the centrality of oratory to the majlis. The time devoted to khit̤ābat (usually forty-five to sixty minutes) far outstrips the time devoted to other genres (usually ten to fifteen minutes). Within the physical space of the majlis itself, there are material elements that accord the khat̤īb an esteemed place in ritual proceedings. The khat̤īb climbs a minbar, a short flight of steps used as a pulpit, to deliver his oration. This sitting down of the khat̤īb is in distinction to the status accorded to other performers, with the small exception of salām-reciters, who either share the floor with the audience or are seated upon a low-lying takht (a small stage or platform, raised from the ground to roughly less than half of the height of the minbar). There is some evidence that the practice of sitting down on a minbar while orating has its origins in the courtly cultures of ancient Middle East (Retsö 2020). This portrayal of the orator in a kingly manner thus draws upon longstanding genealogies of monarchs performing legitimacy for an audience. In the Shiʿi context, the top step of the minbar is also left vacant in deference to Mahdi, the twelfth Imam, who Shiʿa believe resides in occultation. This custom therefore indicates the prominence of the minbar as an object in and through which legitimacy, divinely appointed and otherwise, is routed. In addition, the minbar is often the only piece of prominent furniture in the ritual space, and the elevating of the khat̤īb, literal and figurative, also serves to direct the gazes, literal and figurative, of the audience onto the elevated khat̤īb. Figure 1 illustrates these material dimensions, with the khat̤īb Shahenshah Naqvi seated prominently on a minbar, addressing a majlis in Karachi, in May 2019.

Ideologically, the centrality of khit̤ābat is also evident through three attitudes I encountered in the field. In the months leading up to Muḥarram, devotees routinely discuss among themselves which khat̤ībs are speaking where in the city and on what topic. In these discussions, specific places of ritual practice are only as important as the khat̤ībs they attract. The devotees also frequently reference the majālis not by the actual start time of the majlis but by the time that the khat̤ībs are scheduled to take to the minbar; this has the effect of reducing the majlis to only khit̤ābat, over and above the other segments mentioned earlier. When khat̤ībs enter the majlis, devotees already present and listening to other performers often get up and make way for the khat̤īb. They do so while acknowledging him with a curt bowing of the head and a lifting of their fingertips to their forehead. This getting up and making way is a behavior never utilized for other performers in the majlis except for a select few prominent individuals. These dispositions mark the esteem conferred upon the genre and its performers.

Typologies of oratory

Though khit̤ābat (oratory) proliferates in contemporary Urdu Shiʿi ritual practice, its performance is constantly contested in emic discourse. Shiʿa devotees classify khit̤ābat in two distinct ways. First, khit̤ābat is classified as a relative category that can only be evoked in opposition to other modes of public speaking, such as ẕikr (to recollect) and waʿz̤ (to caution). Here, khit̤ābat is situated on par with ẕikr and waʿz̤, but none of the genres are elaborated further. Second, it is considered an encompassing category where it is also important to attend to the type of khit̤ābat under consideration. Here, some specific forms that constitute khit̤ābat include rowẓeh-khwānī,[13] wāqiʿah-khwānī,[14] and ḥadīs̱-khwānī.[15] A modality of this typological debate is the genre of majlis poster art in which orators are introduced with a wide and deliberate variety of titles—khat̤īb, ẕākir, maulānā, ʿallāmah, ʿālim, and research scholar [sic].[16] In this section, I argue that ontological discussions of khit̤ābat and the concomitant titulary politics, both fraught with classificatory concerns, are an instantiation of emic debates over conceptualization of khit̤ābat and khat̤ībs. The devotees’ reflexive attention to khit̤ābat demonstrates that the devotees do not only partake in the practice: indeed, they are aware of, and invested in, explicitly theorizing khit̤ābat.

Let me give two brief examples that are particularly productive for thinking through the debate in Karachi over the forms and contents of khit̤ābat. First, linked directly to the emic typological debates around khit̤ābat, is what genres of speech ought to constitute khit̤ābat. Arguments abound on whether khit̤ābat should deal with the faẓāʾil (virtues of Imams), maṣāʾib (narratives of the sufferings of the Imams), akhlāq (ethical discourses), naṣīḥat (advice), ʿilm (knowledge), and many other categories, each of which is arguably hard to delineate and divorce from all other categories. This debate is not merely theoretical but also erupts regularly in Shiʿi oratorical practice. In Karachi, khat̤ībs are often asked—by various parties, including, but not limited to, majlis patrons, audience members, and fellow orators—to refrain from evoking one genre of speech or the other. A noteworthy incident in the late 1990s was when Talib Jauhari, arguably Pakistan’s most well-known orator then, was requested by the majlis organizers to stop reciting faẓāʾil and to focus more on naṣīḥat in his addressing of the Muḥarram majālis at Nishtar Park (I. ʿAbbas Naqvi 2020).[17] On the first of the ten days he was scheduled to speak, Jauhari began his oration by sharing with his audience the restriction that had been placed upon him. Jauhari followed up his grievance by drawing upon two authoritative textual sources for the Shiʿa—the ḥadīs̱-e kisāʾ (see note 6) and the genre of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ (stories of the prophets). Jauhari noted that the ḥadīs̱-e kisāʾ was Allah recounting the faẓāʾil of ʿAli, and that the entire genre of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ was Allah recounting the faẓāʾil of other important Islamic figures, those of the various prophets and messengers. In doing so, Jauhari did not merely outline his position on this question of what constitutes proper content of khit̤ābat: he drew upon the established and accepted authority of textual genres to render invalid the majlis organizers’ vision for khit̤ābat. This vignette demonstrates the contestation over emic categories of experience, illuminates the continuous theorization of what constitutes khit̤ābat, and the wider ideological, institutional, and pragmatic contexts under which such debates take place.

Second, Shiʿi devotees, orators, and laypeople alike are heavily invested in policing the honorifics with which orators are identified. In an oration I attended in April 2021, the orator posited a binary between himself and the ʿulamaʾ, a binary that many of his fellow orators would discredit because they consider themselves as members of the ʿulamaʾ. Historically, the category of ʿālim (pl. ʿulamaʾ) has denoted institutional training rooted in the religious sciences (Zaman 2002). The emic questioning of this category in Karachi, through its application to orators who have not been formally trained at a madrasa, is doubly productive. The relatively widespread undermining of traditional modes of learning, in some of the Shiʿi circles I work with, bears structural analogies with modernist and Islamist projects (Zaman 2002; Robinson 2008). Overlaps, rather than differences, among the myriad groups who each lay a claim to the Islamic tradition thus become fruitful avenues of inquiry. Additionally, these local calls for increased flexibility in who constitutes the ʿulamaʾ can also be read as the emergence of new religious intellectuals (Anderson and Eickelman 1999). These individuals, through their presence and work, call for a reconsideration of the ʿulamaʾ as a widespread and pervasive category of analysis and experience.

This debate around who is an ʿālim and who is merely a ẕākir or a khat̤īb exists at the level of orators, who engage in overt and covert considerations of which category their fellow Shiʿi orators can be placed within. This debate also exists at the level of audiences, who have varied but marked evaluative schemes of who they consider an acceptable orator or an ʿālim (Hyder 2006, 43–45). This classification is descriptive and normative—the titles do not simply reference the scholastic achievements, or lack thereof, of a particular orator, but they actively circumscribe the orator as well as the title by delineating the exact ideal-type that the chosen category exemplifies. Zamir Akhtar Naqvi, another prolific orator in Karachi, was perceived by the devotees in two distinct manners. He was, simultaneously, a favorite ʿālim of one socioeconomic demographic in Karachi while also being vocally disowned, by being referred to dismissively as just a khat̤īb, by many other members of the Urdu-speaking Shiʿi community. To be clear, Naqvi’s oratorical style and content remained remarkably consistent in a career spanning almost five decades. What, then, led to Naqvi’s “rise” and “demise” over and above the shifting preferences of the audience? How does attention to Naqvi and his orations illustrate the typological concerns around khit̤ābat? Naqvi’s changing fortunes are not simply explained through reception or audience preferences but through a more nuanced attention, by orators and devotees, to the typologies of oratory: what is khit̤ābat is a constant point of discussion in emic discourse and practice.

One brief instantiation of such a contention is evident in Agha Ashhar Lakhnavi’s Taẕkirat al-ẕākirīn (1946), a fascinating compendium of Urdu-speaking Shiʿi oratory in mid-twentieth-century North India. Though authored in pre-Partition Lucknow, the text relates directly to Urdu Shiʿi ʿazādārī in contemporary Karachi through the continued oversized influence on contemporary ritual practice of ideas and orientations hailing from Lucknow. Long recognized as one of the “centers” of Shiʿi British India, Lucknow’s self-imaginations as the birthplace of a distinct etiquette (ādāb), civilization (tahzīb), and culture (tamaddun) found a place in the nostalgic imaginations of Urdu Shiʿi migrants to Karachi at the onset of, and in the decades subsequent to, the Partition of 1947 (Shahid Naqvi 2002). The Taẕkirah, Lakhnavi details in the preface, is motivated by the utter lack of recognition by lay persons of the crucial efforts of ritual orators to sustain the memory of Karbala. As such, the text attempts to holistically detail the then-contemporaneous orators and oratorical networks, in North India and beyond. The text begins with a sweeping overview of the rhetorical cultures of Islamic history (Lakhnavi 1946, 6–25). This historical description itself, however, is interspersed with close attention to the categories of oratory. For example, in thinking about Muhammad as an orator, the text observes that though the aḥādis̱ (prophetic sayings, assents, and approvals) of Muhammad proliferate, these are mere words (makālmāt): prophetic endeavors must have necessitated the need for extended oratorical events (mabsūt̤ taqrīroṉ) that were not recorded except for a few well-known examples (ibid., 6). Already from the first few sentences of the text we can evince Lakhnavi’s careful distinction of the signifiers with which he is referencing oratory.

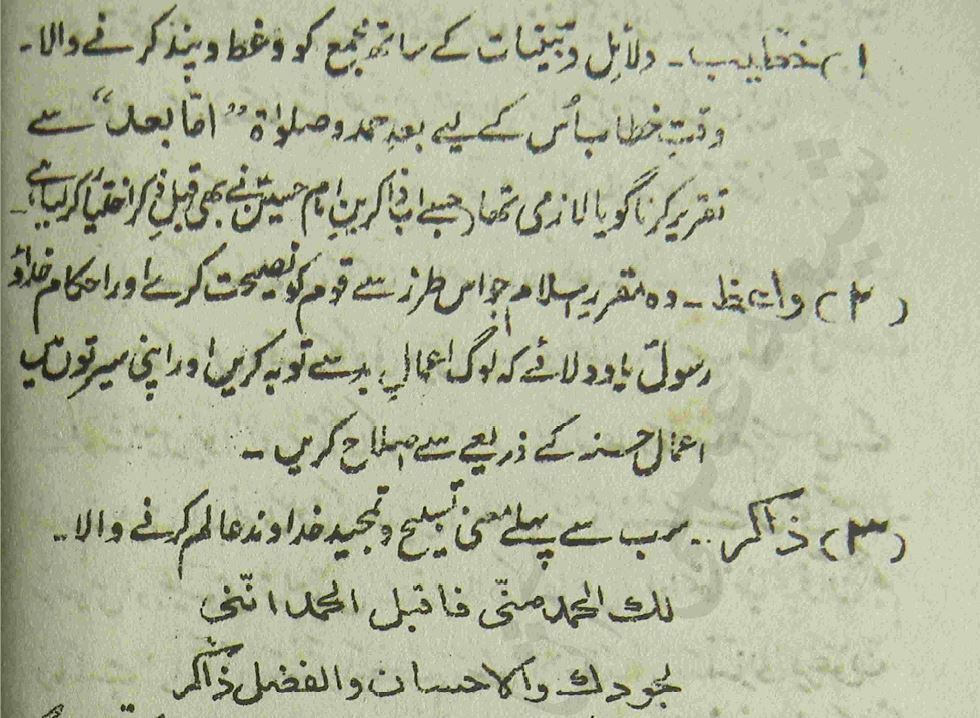

Just to be clearer about the distinctions within ritual oratory, the text also offers a typology, presented in figure 2, that identifies and defines the categories of khat̤īb, ẕākir, and wāʿiz̤. A khat̤īb utilizes rational evidence (dalāʾil-e ẕihnīyāt)[18] to caution and counsel (waʿz̤ wa pand) and begins, after the praise of God (ḥamd) and salutations to Muhammad and his family (ṣalawāt), with the Arabic phrase “ammā baʿad” (here is what comes after). The phrase “ammā baʿad” is a prominent marker in Islamic oratorical practice generally (Qutbuddin 2019). For the Shiʿa, it establishes a clear rhetorical genealogy by linking the present moment with that of the past. A wāʿiz̤ offers naṣīḥat (general advice) in such a manner that, along with his reminders of the rules of God and his prophet (iḥkām-e khudā wa rasūl), people repent from their bad deeds (āʿmāl-e bad) and turn to good deeds (āʿmāl-e ḥusnat) to rectify (iṣlāḥ) their selves (sīratoṉ). A ẕākir first defines, glorifies, and extols God (maʿnī, tasbīḥ, tamjīd) before reminding people of the event of Karbala. Lakhnavi notes that ẕākirs have adopted the custom of prefixing their oration with “ammā baʿad” as well. Having outlined these basic distinctions, Lakhnavi then offers some additional details, over the next page or so, about each category, all the while trying to differentiate one ritual performer from the other. For instance, a small section on the differences between khit̤ābat and waʿz̤ (khit̤ābat o waʿz̤ kā farq) is a good example of this style of writing (Lakhnavi 1946, 8). Though this section is apparently intended to build on the typology introduced above, this section, arguably, does not so much distinguish neatly between the two categories of khit̤ābat and waʿz̤ as constantly threatens to unravel the very distinctions that the typology had first outlined!

Lakhnavi’s classificatory attempts in Taẕkirat al-ẕākirīn evince a clear preoccupation with ensuring that form and content of a given oratorical practice help categorize the type of ritual speaking under consideration. However, the text also evinces a clear confusion over where, exactly, do boundaries between these performative modes lie. This permeability is thus seen both as a threat as well as an opportunity. The threats exist both analytically and performatively. Analytically, the devotees might confer a title upon a ritual performer that is not concordant with the form, content, and context of the genre—Lakhnavi draws upon some local examples to help illustrate how khit̤ābat and waʿz̤iyyat can overlap in a speaker’s repertoire (Lakhnavi 1946, 10). He does so after having established a clear historical hierarchy in which he suggests that khit̤ābat was always considered more authoritative than waʿz̤, at least in the Arabic-speaking world. The seeming proliferation of waʿz̤ in Hindustan, Lakhnavi suggests, is not so much reflective of a lack of oratorical quality but simply a result of the popularity of waʿz̤ among Iranian ʿulamaʾ who were influential in the spread of Shiʿism to the subcontinent (ibid., 9). The performance might fail because the orator is unable to elicit memory and emotion from the audience: this is especially probable if there has been a prior analytical mismatch in the title awarded to an orator and the orator’s own repertoire. There also exists, however, an opportunity for authors such as Lakhnavi, and for the devotees at large, to utilize this permeability of genres to argue for a particular ritual orator as being one or the other. That is, the absence of clear delineations between a ẕākir and a khat̤īb makes possible instances such as the dual perceptions of Zamir Akhtar Naqvi—simultaneously an ʿālim for one demographic but merely a khat̤īb for another demographic—from earlier in the article. Indeed, the very presence of the term “ẕākir” in the title of Lakhnavi’s text itself, when juxtaposed with the typologies of oratory that the text introduces, is instructive of the capaciousness of these categories—the title of the text simply flattens all of the typological work that the text subsequently undertakes.

“Husain’s University”

Having discussed the categories through which orators and oratory are evoked, I now wish to turn to textual and ethnographic examples that foreground the epistemic dimensions of Urdu Shiʿi oratory. In particular, I want to highlight that “Husain’s University” is more than just a sign: in practice, orators regularly draw attention to their taḥqīq (research) skills to posit themselves as engaging in active and new research, develop clear and identifiable semiotic and semantic repertoires, and are invested in producing the very “Husain’s University” under the auspices of which they consider themselves speaking. I bring out each of these aspects of contemporary ritual oratory because they demonstrate that the genre is much more than just a “sermon” or “religious” edification: khit̤ābat is contingent upon the social and historical structures within which it exists, and to which it responds. Situated within a broader historical milieu in which traditional religious genres and actors are often the targets of critiques emanating from competitors such as modernist and Islamist movements (Zaman 2002, 7–10), the idiom of the university and the array of concomitant research and citational practices help provide a vocabulary through which orators lay scientific, if not secular, claims to knowledge (Robinson 2008).

A visible and representative example of the preoccupation with research was a Shahenshah Naqvi oration I attended in August 2021. The event itself was part of a larger series of the Muḥarram ʿashrah, one of the four that Naqvi was addressing all over Karachi. I had already noted, in earlier orations in the series, some repetition of content. Though I was apt to notice such repetition because of extensive fieldnotes that I had compiled over a period of two years, the lack of new content was also a prominent concern for my interlocutors in some informal conversations I had with them after the first few events in this particular series. It was not coincidental, then, that on August 16, 2021, during the seventh oration in the series, Naqvi said “yahīṉ baiṭh kar mujhe jumle nahīṉ āte, aik ghanṭe kī taqrīr ke pīche das ghanṭe shāmil haiṉ” (I do not come up with sentences while sitting here, an hour of speech is backed by/inclusive of ten other hours). The quantification of the labor hours that go into preparing for an event is noteworthy for many reasons. Such a concrete figure disrupts the usual rhetoric around the oration as solely inspirational and spontaneous, a narrative used consistently in comparable performances, such as the Banarsi kathā (Lutgendorf 1991, 181–82). The idea of a wide range of research producing a proportionally smaller range of usable content is also familiar, especially to the readers of this article. The suggestion that Naqvi devotes significant time to his research is also meant to bolster his own scholastic profile—orators regularly get dismissed by the institutionally based ʿulamaʾ, and by the scholars that study Islam, as not possessing “authoritative” knowledge. Of course, Naqvi here is also challenging other orators with whom he competes by laying down a clear standard: Naqvi wishes to make public his commitment, even if merely rhetorical, to research so that devotees can appreciate his time and effort, especially in comparison with his contemporaries.

If Naqvi stands at the center of the narrative he wishes to produce, let me also turn to Talib Jauhari’s trajectory as an orator, a trajectory that is often described to me by interlocutors as a tale of two halves. Jauhari enjoyed immense success and visibility in the 1980s and 1990s, but the early 2000s marked a decline in his audiences. Long-term listeners voiced their dissatisfaction with his style of oration. Indeed, it was not uncommon for devotees to prefer cassettes of Jauhari’s recordings from the earlier part of his career over and above his then-contemporaneous orations. For reasons publicly stated to do with Jauhari’s health, but presumably also because of a lack of demand for his style of oration, Jauhari took a self-enforced sabbatical and disappeared from the public eye. When he returned to oratory in the late 2000s, he was equipped with brand-new materials. Jauhari proceeded to recapture the more visible oratorical events that had slipped through his grasp, and devotees applauded his efforts at remaking himself through new research. Jauhari could not hit the highs he had had in his first stint as an orator but managed, nonetheless, to re-establish his claim to being a forceful orator, a claim that he staked with regularity until his death in 2020. In the figure of Jauhari, then, we see another privileging of this idea of fresh research, even as it emerges from the demands of the devotees rather than the orator himself.

Research cultures, of course, give rise to specialized knowledge. For example, Jauhari was considered, almost unanimously by his peers, as an authoritative mufassir (commentator) of the Qurʾan (Kazimi 2021). This had to do with his linguistic expertise, his formal training in Iraq, his widely acclaimed TV show Fahm-e Qurʾan (An Understanding of the Qurʾan), and his mastery of tafsīr literature. Ayatollah ʿAqeel al-Gharavi, an Indian orator who has spent considerable time orating in Karachi, both by virtue of his qualification as an Ayatollah and by the distinct form and content of his oration, is often heralded as rhetorically dense, accessible only to an audience that has a strong grasp of formal registers within Urdu. These associations of orators with particular areas of inquiry emerge out of an appreciation of, as well as a demand for, the epistemic dimensions of oratory by Shiʿi devotees (Nath 2013, 69). Yet, the orator’s grasp of a particular subject matter is no guarantee of the content’s reception. Both Syed Akbar Hyder and Rizwan Zamir recount the notable incidents of Ayatollah ʿAli Naqi Naqvi being the target of public scrutiny after the first edition of his now well-known biography of Husain was published in the mid-1940s (Hyder 2006, 80; Zamir 2011, 221–22). Zamir Akhtar Naqvi, famous among his well-wishers for his historical anecdotes, was often derided by other orators and devotees for the very narratives that endeared him to a sizeable populace in Karachi.

The transmission of scholastic knowledge to a lay, but not passive, audience lays bare one particular mechanic of how orators and their audiences interact through citational practices evoked in service of an oratorical demonstration of knowledge. Even as orators differ over what constitutes appropriate content for khit̤ābat, they share in the practices through which they present and perform their conceptions of khit̤ābat. On the oratorical end, the very argument for the presence of ʿilm (knowledge) in khit̤ābat is itself one ideological position, often juxtaposed against wāqiʿah (incident). A representative position is that of Zuhair Abidi, who suggests that all Urdu Shiʿi oratorical events can be approached through this dyad of ʿilm and wāqiʿah (Abedi 2021). For instance, orator Kazim ʿAbbas Naqvi stressed at an oratorical event that khit̤ābat must only ever be ʿilmī (knowledge related)—anything else is unfair to the minbar from which the oration is being delivered (K. ʿAbbas Naqvi 2021). This is in stark contrast to the public laments of Shahenshah Naqvi, who has expressed that the loss of public munāz̤arah (theological-juridical disputation), a genre of religious interaction that permeated North India and Punjab from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, has necessitated the use of khit̤ābat as a medium of disputing competing theologies (Shahenshah Naqvi 2020).

Regardless of which of these orientations get privileged in a given oratorical event, what is important is that these are all undergirded by similar citational practices. Orators of both ilk—ʿilmī and wāqiʿātī—actively provide sources that serve myriad functions. A citation establishes the credibility of the claim being made by providing an ostensibly trackable reference; a grasp of textual sources demonstrates the scholastic prowess of the orator; and, perhaps most importantly, the citation helps satisfy the modern preoccupation with the origins of a claim. It is this attention, even if merely performative, to citing the sources that provides “Husain’s University” with a semantic base. Whether these citations are specific or deliberately ambiguous is beside the point—it is the very fact that orators engage in the act of citing their sources that is worthy of attention. The most common citation is that of the Qurʾan, and orators provide both specific chapter and verse citations as well as more general references to the text. The very structure of modern khit̤ābat itself is predicated on a citation of the Qurʾan—in the formulaic recitation that marks the beginning of the oratorical event, after the ḥamd and s̱anāʾ, the khat̤īb utilizes the aforementioned ammā baʿad as a prefix for a Qurʾanic verse.[19] After the Qurʾan, it is the vast ḥadīth corpus that gets cited. Here, orators draw upon not just Muhammad but also the twelve Imams. Importantly, orators do not restrict themselves to Shiʿi ḥadīth collections such as Biḥār al-anwār (discussed shortly) or al-Kāfī, but equally draw upon Sunni compilations, particularly those of al-Bukhari and Muslim. In both cases, however, the mastery of the corpus is performed for an audience that appreciates more than just the contents of the ḥadīth. The audience also appreciates the ability of the khat̤īb to make accessible and concrete, through citational practices, otherwise specialized and distant genres of work.

Muhammad and the bee

Let me illustrate the intertwining of the many threads I have opened through an anecdote I encountered multiple times in my fieldwork; I begin with continuing my observation about vague citational practices. Two orators, in two different parts of the city, hailing from two different parts of the country, and at two different times of the year, narrated the exact same anecdote for which only one of them provided a citation. The citation provided was thus: “It is written in Biḥār al-anwār.” Biḥār al-anwār is a seventeenth-century Arabic ḥadīth compendium of more than one hundred thousand Sunni and Shiʿa ḥadīth, spread over twenty-five original volumes, that constitutes an authoritative textual source in contemporary Shiʿi thought and practice (Kohlberg 2020). While this open-ended and vague reference to a voluminous text is frustrating for the scholar, this style of citation is nonetheless performatively efficacious because of the existing respect for, and an understanding of the place occupied by, Biḥār in the minds of the audience.

The anecdote itself revolves around Muhammad and a bee. Muhammad was addressing the ṣahābah (Companions) when they were distracted by the buzzing of a bee. One of the Companions inquired if Muhammad could ask the bee some questions about the production of honey. Muhammad ordered the bee to speak and to respond to the questions being posed. The Companion asked the bee to inform those gathered what makes honey sweet given that the ingredients that go into honey are bitter? The bee replied that it recites durūd, salutations on Muhammad and his family, to make the bitterness of the ingredients go away and that it sends laʿan, curses on the enemies of Muhammad and his family, to give the honey its characteristic sweetness. The Companion then asked the bee about quality control: how do bees make sure that the ingredients they use in the production of honey are not harmful in the final, edible product? The bee replied that it stands guard at the entrance to the hive and ensures that all ingredients being brought in are free of three specific attributes—these include najāsat (impurity), ghilāzat (filth), and ḥarām (prohibited). After a couple of other questions, the Companions were satisfied, and Muhammad allowed the bee to leave.

Despite its brevity, this anecdote is worthy of attention because of the richness of the themes that dominate its form, content, and context. Formally, the semiotic presence of signifiers such as the bee and honey are easily associable with the Qurʾan, the one text that all contesting claimants to being Muslim agree upon. In particular, the anecdote draws upon the Chapter of The Bees (Al-Naḥl), which is the sixteenth chapter in the Cairo edition of the Qurʾan. The dialogical presentation of this anecdote—especially the question-and-answer style, perfected in Shiʿi vignettes of their sixth Imam, Jaʿfar al-Sadiq—also mimics an interactional form with which audience members are already familiar. The Qurʾan regularly employs such a strategy (Christiansen 2020, 95–96; Hoffman 2020), the ḥadīth often show Muhammad and the Companions engage in a similar back-and-forth, and Shiʿi memories of their Imams frequently harken back to modes of questioning, between the Imams and their audiences, that allow the Imams to demonstrate their knowledge of the unseen. The structures of speaking that dominate contemporary South Asian Shiʿism are situated in relation to the modernist rhetoric of evidence and reason. Anecdotes of the miraculous or the enchanted do not simply rebut the claims for proof but conform themselves, through their use of interactional forms such as the question-and-answer model, to these modernist demands. The questioning through which the bee is made to account for its activities is as equally important as the contents of the bee’s answer. Additionally, as Kirin Narayan has shown in the context of western India, storytelling is a compelling vehicle for religious instruction—the narrative of Muhammad and the bee are presented in a form that makes them easy to digest, remember, and transmit for the audience (Narayan 1989).

Substantively, this anecdote takes deep-rooted and elaborate theological doctrines and presents them in an accessible manner. This presentation, however, is not neutral but colored thoroughly by a disputational style. The anecdote is also indicative of the impossibility of separating ʿilm (knowledge) from wāqiʿah (incident), as some contemporary orators referenced earlier were wont to do. Additionally, the anecdote also productively interrogates the claims of the orators, such as Kazim ʿAbbas who I referenced earlier, who wish to bracket the public undermining of rival theologies by distinguishing clearly between what constitutes knowledge qua knowledge and knowledge in service of undermining the claims of the other. Such a task is simply not possible—the normative commitments of persons, ideas, texts, and the like cannot exist with ignoring their competitors wholesale. In this anecdote, the bee’s recourse to durūd and laʿan stands in for the Shiʿi practices of tawallā and tabarrā—praising the virtuous and cursing the condemned—as natural and integral parts of the functioning of the universe.[20] Tawallā and tabarrā are not simply commands to be followed by the Shiʿa but are woven into the very world, by virtue of their instrumentality to the mundane acts such as the production of honey, that the Shiʿa occupy. Audience members are advised that to give up tawallā and tabarrā, a demand regularly made of Shiʿa in recent Pakistani—as well as twentieth-century British Indian—history including at the time of the writing of this article, is as unnatural as bitter honey.

Similarly, the idea that the bee filters out various levels of ritual impurity, najāsat, ghilāzat, and ḥarām, is a commentary on notions of pure genealogies of the Shiʿa, a product of distinct ontological composition of not just the Imams, but their devotees as well. Indeed, such ideas proliferate in Shiʿi texts as well as in everyday rhetoric, including that of oratory (Majlisi 1983). Audience members of a given khit̤ābat are already aware of these theological concepts, largely because of their structured and durable, to use Bourdieu’s terms, exposure to such oratorical events from childhood (Bourdieu 1991). Khit̤ābat then is not merely or always a source of new information but also a validation of the knowledge that audience members bring to the event. To be clear, historical information, in its positivist sense, such as that to do with persons or events, can be completely new, especially if the orator is drawing upon specialized historical or historiographical works. However, conceptual information, to do with ideas or doctrines, is often already circumscribed by broader ideological and social structures.

Contextually, this anecdote must be embedded within the broader events at which it was recounted, as well as within the structural context of oratory in contemporary South Asia. For the former, at both events in which I listened to this anecdote, the context was colored by discussions of wilāyat, or the Shiʿi notion of authority that ʿAli was invested with by Muhammad. These discussions in the public sphere are not merely commemorative. There is no doubting that they serve an edifying purpose, as both Vernon James Schubel (1993) and Toby M. Howarth (2005) have noted in their attention to ritual oratory in Karachi and Hyderabad, respectively. These discussions are also rejoinders to broader challenges leveled at the Shiʿi, including their allegiance to ʿAli over and above that of the early caliphs. I concur here with Schubel and Howarth that this public discourse operates at two levels—that of the orator and that of the audience (Schubel 1993; Howarth 2005). The orator provides his audience with anecdotes, such as the aforementioned Muhammad and the bee, that can then be invoked by the audience in their own public and private engagements with non-Shiʿa. However, I also want to note that there is a third level here in which the orator, by recounting this anecdote, carves an epistemic space for himself in competition with groups like the ʿulamāʾ. Neither of the orators who narrated this anecdote were formally trained as an ʿālim. However, the presentation of core theological doctrines such as wilāyat, in conjunction with the emphasis on original research and the ubiquitous use of citational styles, helps orators bolster the questioning of the category of the ʿulamāʾ that I observed earlier in the article. Importantly, it is often the figure of the orator that is accessible and present to Shiʿi devotees in Karachi, over and above an ʿālim confined to a scholastic institution.

Each of the formal, substantive, and contextual aspects of this narrative fleshes out the epithet “Husain’s University.” The existing scholarly approaches to Urdu Shiʿi khit̤ābat would give primacy to the referential functions of the anecdote, such as the presentation of tawallā and tabarrā, or wilāyat. That is, what does the orator mean or intend through their use of specific signifiers? In contrast, by attending to questions of form and context, I wish to highlight the ideological functions of Shiʿi khit̤ābat. The anecdote of Muhammad and the bee is interesting on its own, but more so when embedded within the contestation for authority that orators are engaged in with other sources, whether textual, such as the Qurʾan and the ḥadīth, or personal, such as the ʿulamāʾ or the modernist.

Conclusion

The title of, and epigraph to, this article brought together two distinct signifiers—Husain and university. I unpacked “Husain’s University” to examine how devotees in contemporary Karachi partake in emic taxonomic debates over oratory. These debates are not merely theoretical but undergird, and emerge in, ritual oratorical practice. I argued that contestations over who is an ʿālim and who is merely an orator are productive because of the continuities they reveal not just in Shiʿi thought and practice, but also the overlaps of the Shiʿa discourses with Islamist and modernist rhetoric. My attention to khit̤ābat highlights the central role that ritual practice plays in mediating the devotees’ access to ideas, events, and persons from Shiʿi historical narratives. This mediation, however, is not monodirectional. Devotees, even as they engage in ritual practice, are consistently and consciously engaged in theorizing ritual practice itself. To this end, my article is best read as suggesting that attention to emic conceptualizations of a practice must account for the traditions of debate that accompany a practice. In this way, we begin to inquire into both the importance attributed by devotees to, and their concomitant practices of, emic classificatory cultures.

I am grateful to Karen Ruffle for inviting me to contribute to this special issue, and for her careful eyes and ears to the ideas contained herein. All errors and omissions are solely mine.

Here, I am indebted to Tony Stewart’s (2001) work on religious encounter. Stewart’s equivalence-making captures the approximation that speakers attempt in their use of signifiers from two different lexicons. Orators such as Naqvi regularly engage in such equivalence-making, especially in their use of English terms to analogize existing practices of Twelver Shiʿa in Karachi.

It is pertinent here to note that the signifier “ẕākir,” if it is abstracted from the particularities of its contexts, is a generic term that captures both poetic and prosaic performers of the Karbala narrative. In Karachi, while this broad usage retains a general presence, it is far more common to use ẕākir to indicate a ritual orator, especially in contradistinction to other competing categories. I elaborate on this later in the article.

Though soʾyam and chihlum translate to “third” and “fortieth” respectively, these commemorations, especially the chihlum, do not overlap with the actual number of days between the death of the individual and the commemoration. Instead, these labels figure as general temporal markers, indicating that “some time” has passed, with the specificity of “some time” not a literal concern for the devotees.

Shiʿi historical narratives depict all of the Imams, as well as Muhammad and Fatimah, to have been martyred by their enemies.

I have focused here on the mardānī (male) majlis. The zanānī (female) majlis, generally held in the domestic sphere but also lately, in Karachi, in leading imāmbārgāhs, is not open to men who have crossed the threshold of puberty. Additionally, and arguably, the zanānī majlis necessitates a different analytical framework, especially given the relationship of the zanānī majlis to the early childhood formation of the Shiʿi habitus.

The ḥadīs̱-e kisāʾ (the event of the cloak) is a recounting of an event in Shiʿi memory where Allah inquires with the angel Jibrāʾīl about the people (Muhammad, ʿAli, Fatimah, Hasan, Husain) gathered within a cloak. The recitation of the ḥadīs̱-e kisāʾ marks the formal beginning of a majlis in Karachi. Based on the scholarship on the Hyderabadi majlis by Pinault and Hyder, the ḥadīs̱-e kisāʾ does not figure in the Hyderabadi practices. The ḥadīs̱-e kisāʾ is also conspicuously absent from Schubel’s fieldwork in Karachi in the early 1980s—this absence is consistent with the recollections of my interlocutors that the ḥadīs̱-e kisāʾ in the Karachi majlis is a “new” phenomenon, only three or four decades old.

Soz is the melodic chanting, by a group of three to five individuals, of Shiʿi devotional poetry written in various meters. Soz can be dated to nineteenth-century Lucknow, where it emerges as a replacement of the recitation of the more formal and elaborate mars̱iyah.

Salām is a Shiʿi devotional poem that is generally, but not always, written with a monorhymed scheme. See Hyder (2006) for a more detailed description.

Khit̤ābat is the ritual oratorical practice that this article discusses. Importantly, I choose the signifier “khit̤ābat” to refer to oratorical practice. Khit̤ābat reflects a more neutral category that does not carry the connotations, positive or negative, with which terms such as “ʿālim” and “ẕākir” are inflected.

Nauḥah is a short, rhythmic poem, to the tune of which devotees perform mātam (self-flagellation).

Ziyārat, literally visitation, is a turning toward the tombs of Husain, Raza, and back to Husain while offering greetings and acknowledgments to Husain, Raza, and Mahdi.

Rowẓeh-khwānī began as the recitation of the Rowẓat al-shohadāʾ, an early sixteenth-century Persian text by Husain Vaʿez Kashefī (see Ruffle [2025] and Williamson Fa [2025] for further discussion of Kashefi). The term is also used broadly, in contemporary Persian, to reference ritual oratory.

Wāqiʿah-khwānī refers to a genre of reciting anecdotes or events. While these events might have moral undertones, the use of the term is often derisive, indicating a performance devoid of ʿilm (knowledge), fiqh (law), and other “high” sciences.

Ḥadīs̱-khwānī translates to a “reading of the event.” In contrast to the terms “rawẓeh-khwānī” and “wāqiʿah-khwānī,” the term “ḥadīs̱-khwānī” is fairly prevalent in Karachi.

Karen Ruffle noted that many of her Hyderabadi interlocutors, who doubled as ẕākirs, held a doctorate and professorships in universities across the city. In Karachi, orators with academic credentials from nondenominational institutes of higher study are visible but not common. It is, in fact, quite unusual in Karachi for an orator to hold a PhD. As such, the “research scholar” designation is often used to emphasize the scholastic prowess of an orator who does not have any formal or institutional credential such as “doctor.” Arguably, the “research scholar” designation can also be read as a secular translation of a religious credential, such as a degree from a ḥawẓa or a madrasa.

Nishtar Park is a prominent gathering place in Karachi for large religious and political gatherings, including those of the Shiʿa. While Nishtar Park was arguably a central node of Shiʿa activity before the turn of the millennium, the early twenty-first century has witnessed explosive and influential growth in other parts of the city, thus undermining any claims of Nishtar Park to being a markaz (center). Nishtar Park continues to function as a meeting spot for various Muḥarram processions, but for how long remains to be seen.

I am indebted to Baqar Mehdi (IBA), Ali Raj (Columbia), and Shiraz Ali (Berkeley) for their thoughts on the second term in this construction. We debated reading this term variously—dīnīyāt, bayānāt, and ẕihnīyāt. We also discussed the possibility of a misprint. I have opted to read this term as ẕihnīyāt. Importantly, it is the dalāʾil here that should capture our attention. This is because dalāʾil indexes the emphasis on evidence and reasoning that I discussed earlier in the article.

On occasion, I have witnessed the verse replaced by a ḥadīth of Muhammad, and once by a ḥadīth of ʿAli. However, it is the Qurʾan that looms large in this preface to the actual oratorical event.

Though tawallā and tabarrā proliferate in contemporary Shiʿi theological discourse, their historical presence in theological texts and practices is far more convoluted. See the tabarruʾ entry in Encyclopedia of Islam, (Calmard 2012). For our purposes, the following remarks on the Urdu version of Ayatollah Khomeini’s website (Khomeini 2015) suffice.