The funeral rites begin when the nanfu master[1] steps toward the altar, dons his crown, and fastens a strip of embroidered cloth. The family’s eldest son stands beside the symbolic “burning hell,” a structure made of nine unfired tiles, each one representing one of the nine courts of the underworld that a soul must cross before reaching the final court, where its fate will be decided. In his hand, he holds a soul tablet: a thin sheet of paper inscribed with the names of the deceased, ready to be offered to the flames.

The master then picks up a sword from the altar, sticks it into a pile of joss paper and sets it alight. Holding the flaming sword like a baton, he performs a dance around the burning hell while brandishing the sword violently and hopping up and down in rage. Other nanfu masters follow him in his dance, running in and out of the scalding hell. Each of them holds a cymbal in their hands. A musician accompanies the dance with drums (fieldwork observation, funeral conducted at 19a Tiong Bahru Road, Singapore, September 16, 2019.)

Dressed in saffron and canary yellow robes, and chanting in Cantonese, five nanfu masters perform a sacred rite, po diyu (Breaking the Netherworld Gate), during a funeral at a void deck, an open area on the ground floor of public buildings owned by Singapore’s Housing and Development Board (HDB) that act as a communal space for activities such as funerals, wakes, and weddings. This rite is the core component of the Cantonese funeral ritual, which aims to break the Netherworld’s gate, save the deceased, guide the soul of the deceased in its walk through hell, and facilitate their entry into the cycle of reincarnation. Marjorie Topley (2011, 61–62) states that the origin of this rite resides in the Buddhist legend of Mulian who rescued his mother—an explicit nod to the Confucian value of filial piety.[2] This rite mirrors the syncretic nature of Chinese religion, which cuts across the conventional delineations of the sanjiao (three teachings): Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism (Topley 2011, 61–62).

Located at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, Singapore has been home to Chinese migrants from different (Fujian and Guangdong) provincial dialect groups, including Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Hakka, Hainanese, and more, since its establishment as a British trading post in 1819. As Chinese migrants in Singapore began forming local communities, death rituals became an indispensable part of Chinese social life and required religious specialists who could conduct funerals in these languages. Tong Chee Kiong notes that the Chinese in Singapore are highly attached to death rituals because they believe in the bonding between the living and the dead (Tong 2004, 1–2).

From the early days of Chinese settlement in Singapore, Daoist priests were invited to perform elaborate rituals that showcased the distinctive speech characteristics of each dialect group. Today, every Singaporean Chinese dialect group boasts Daoist priests who conduct rituals in their respective languages (Dean 2016, 227–28). The rituals are not only a cultural and social process that allow the deceased’s family to actively and convincingly engage with the spiritual world but are also a manifestation of the dialectical identity of Cantonese Singaporeans.

This study of funeral rituals in contemporary Singapore proposes a new understanding of the creation of sacred spaces by focusing on the rituals of the nanfu masters. It seeks to shed light upon the continuity of traditional Chinese rituals—which exhibit a strong affiliation with their place of origin and vernacular dialectical identity—within state-planned HDB areas. Further, it attempts to highlight a concept of “space” that is process-oriented and nonbinary.

The article shows how the funeral rituals performed by the nanfu masters operate within an “unofficial” sacred space which subverts, resists, and compromises Singaporean State policies. In accordance with Lefebvre (1991, 9–11), space is treated not as a neutral receptacle but as a socially produced construct saturated with meanings, social relations, and political priorities. Funerals conducted in HDB void decks transform the State’s “profane” space into a sacred space through the rituals performed by the nanfu masters while preserving the continuity of vernacular identity.

Using data from extensive fieldwork, this article explores how Cantonese identity in Singapore temporarily manifests through the rituals conducted by nanfu masters. It questions the notion of a homogenous identity by demonstrating how human actors experience and deploy multiple, often conflicting manifestations of identity as nexuses for exercising and resisting power, thereby complicating their categorization. While state power frequently constructs and imposes visions of unitary ethnicities in a top-down process, the deployment of labels on the ground reveals how the imagining of identity also has a significant bottom-up component. Funeral rituals, an essential life cycle event, reveal cultural continuity, and particularly Cantonese identity, despite the transformation of rituals’ formats due to changes within Singaporean society.

This study is based observations and ethnographic fieldwork conducted on death rituals in Singapore between 2019 and 2022 that included eight funerals, six of which involved the funeral ritual, either in part or in full. Most of the data were gathered while funerals were in progress; the families of the deceased declined to be interviewed and were not involved. The particulars of the funerals are presented in Appendix 1, which also provides the empirical foundation for the discussion which follows. Void decks are the primary observation area, as five of the six funeral rituals observed were conducted in these areas, while only one was conducted in a funeral parlor.

From Profane to Sacred: The Reconfiguration of Official Space in Singapore

Spaces act as mirrors, reflecting the complex power dynamics shaped by state authority and diverse social actors. Eliade (1959) and Durkheim ([1912] 1995) both argue that power has a spatial dimension. Eliade (1959, 20–21) proposes that sacred space emerges through hierophany—a process formed by the actions and imaginations of its inhabitants—which lies at the heart of place-making. Durkheim ([1912] 1995, 33–39), by contrast, views sacredness as inseparable from ritual performance: it is the repetition of ritual within a space that endows a location with sanctity. In this sense, Durkheim suggests that profane space can be transformed into sacred space. Despite their different approaches to the sacred–profane divide, both scholars show that space is inherently social, political, and cultural in nature.

It should be noted, while both scholars assumed that clear lines can be drawn between notions of the sacred and the profane, recent scholarship by Lily Kong and Brenda Yeoh (2003, 1961–74), Julian Holloway (2003, 211–33), and Orlando Woods (2013, 1062–75) has problematized this dichotomy, particularly in the context of land-scarce Singapore.

Holloway (2003, 1073) suggests that the sacred manifests in everyday life, particularly through embodied performances of sanctification. Meanwhile Kong (2001, 214) addresses the notion that a space designated as “officially sacred” signifies the politics of space, particularly the relationships between secular and religious forces stating “churches, temples, synagogues and mosques, illustrate the power of secular authorities in defining the locations of religious buildings.” According to Kong, official sacred spaces are sanctioned and approved by secular authorities, reinforced by both religious forces and state power.

Sacred space is dynamic in nature; it is not static or unchanging, rather evolving over time. In this respect, Kong (2001, 226) advocates for a more extensive scholarly treatment of unofficial sacred spaces, which include “indigenous sacred sites, religious schools, religious organizations and their premises (communal halls), pilgrimage routes (apart from the sites themselves), religious objects, memorials and roadside shrines, domestic shrines, and religious processions and festivals.” This has led to a broader understanding of the processes of sacralization to include unofficial space associated with religious activities, as noted, for example, in Woods’s (2013, 1069–71) case study of house churches in Sri Lanka. This case study demonstrates that individuals have successfully established sacred religious networks within the regulations and constraints imposed by the State.

While this scholarship focuses on the notions of embodied “sacredness” in profane locations, it does not address the actions and practices of the ritualists. Heng (2021, 5) notes that unofficial sacred space in religious festivities is imaginative, ephemeral, subversive and controlling, imbuing physical spaces with meanings contested by the State as well as by members of society. This article draws on further scholarship to contextualize the repertoire of strategies utilized by ritual specialists in manipulating profane space—strategies that are typically associated with non-religious activities in the Singaporean context, where the island nation is geographically compact, and space is at a premium.

Space has consistently been a battlefield between the Singaporean State authorities and ordinary people since the Colonial era. Yeoh (2003, 1–27) contends that Singapore’s urban development resulted from contests of power and compromises between the Colonizers and their subjects. This remains an integral component of urban planning, redevelopment, and state-building in post-Independence Singapore. Moreover, the State’s dominant narrative of land scarcity has led to a consistently authoritarian approach to space and its usage (Yeoh and Kong 1994, 17–35).

Singapore’s lack of a hinterland has resulted in the adoption of a ruling ideology of survival and pragmatism, as noted by Linda Lim (1983, 757–58). Waller (2001, 47–63) further highlights that the State implemented extensive urban development and landscape planning policies, clearing slums and constructing public housing for residents. Following the development of the HDB and the Planning Department shortly after Independence, citizens moved into the new estates, leaving their kampung (villages). As a result, Singapore’s landscape is meticulously planned and carefully designated for specific purposes. Beyond regulating residential land, the State also determines the size, nature, and use of spaces, including religious spaces, which often face scarcity, regulation, and restriction. Kong (1993, 32–38) notes that Singapore’s religious landscape is highly regulated to align with state ideologies and to reinforce its political rhetoric regarding religion and the freedom of worship.

Chua Beng Huat argues that the idea that Singaporean landscape strategies have resulted in fundamental changes in everyday life practices. According to Chua (1995, 94–99) state policies exert a pervasive influence on the daily lives of Singaporeans, including their religious practices. Consequently, state intervention affects both socioeconomic activities and everyday customs. The State’s efforts to exercise what Michel Foucault (1978, 135–37) famously termed “biopower” include the regulation of religions and related customs. As a result, religious landscapes are often sacrificed for urban planning purposes.

Kong and Yeoh (2003, 75–93) further explain that religious activities must be conducted within residential estates, leading to the sharing of physical space between residential areas and religious activities. According to Kenneth Dean (2015, 273–98), within religious transnational networks, religious space has been both compressed and extended. Dean notes that in Singapore, all levels of political discourse and action permeate every level of lived space, resulting in a flattened and highly concentrated spatial landscape. The HDB estates exemplify this homogenization of space. Nevertheless, religious activities transform these spaces into ritual sensory zones (Dean 2015, 276–79).

The national ideologies of survival and pragmatism are also widely adopted by the Singaporean Government. The socioeconomic aspects of Singaporean society are influenced by state policies and actions, such as the manipulation of “deathscapes” and the performance of death rituals (Lim 1983, 757–58). In Singapore, the dead are viewed as passive actors within the State’s narrative of progress and scarcity; the State has implemented a series of social reforms aimed at compressing traditional death rituals into a simplified and environmentally friendly format, reserving land for the living, and re-orienting new citizens toward adopting national rather than ethno-centric identities (Yeoh 2011, 287–90). This series of social reforms has substantially secularized the spiritual space and time of death (Guan, Woods, and Kong 2021, 9–10). As burial methods change, so too has the nature of commemorative rituals conducted by specialists.

Although the State often leads in constructing the dominant forms of space planning, the use of space is not entirely manipulated or defined by it. Social life is also shaped by moments of entanglement and domination, where human actions generate and are given significant meanings that correspond to state power. Therefore, human agency, as suggested by Helen Siu (2016, 1–2), is not necessarily marginalized and silenced but rather actively negotiates in relation to the State. Heng (2015, 70–74) and Hong Yin Chan (2020, 10–11), stress the dialectical relationship between individuals and Singaporean social structures generally, and religious practices in particular. Secularized space can be transformed into sacred space during religious events through human actions that imbue it with new meanings. In this way, religious rituals continually introduce the sacred into everyday life, blurring the boundaries between the sacred and the profane.

Joanne Punzo Waghorne captures the nuances of human agency in the religious life of Singapore in her study of Hindu-based religious movements in HDB buildings. Waghorne (2021, 1–22) defines the two poles of the Singaporean landscape as the State-secularized “macrospace” and spiritual “microplaces” that exist with the HDB estates revealing the contested and ambiguous nature of space in Singapore. Waghorne reaffirms that secularized HDB flats can be subverted and transformed into a sacred space.

Terence Heng (2016, 215–34) explains how sacred space is constructed through human actions. In his study of spirit medium performances in HDB flats, Heng (2015, 57–78) shows how Chinese spirit mediumship is not actively encouraged by the State on the one hand yet is nonetheless tolerated if its practice does not elicit complaints from other households. The rituals performed on the sides of the roads and streets during the Hungry Ghost Festival (also known as the Zhongyuan Festival in Taoism and the Yulan Festival in Buddhism) subvert state-planned streets into ethnic private spaces reinforcing the diasporic ethnic identities of the individuals concerned. In fact, the getai (Songs on Stage) activities performed during the Hungry Ghost Festival represent a contested category that actively manifests the ethnic heterogeneity of Chinese Singaporeans (Chan 2020, 1–13).

The case studies by Waghorne, Heng, and Chan all illustrate that the concept of space is not rigid but dynamic. “Unofficial” sacred space, as termed by Heng (2016, 217), is not necessarily illegal, deviant, or subversive. Rather, the creation of such spaces, as these scholars suggest, represents a form of tacit resistance to state policy—one that has been reluctantly acknowledged and permitted by state authorities.

Drawing on this scholarship, this article seeks to highlight the significance of human actions by downplaying the conceptual dichotomy of power and resistance, even as it stresses the twin processes of negotiation and complicity. The use of space is not entirely manipulated or defined by the State, rather, secularized space has the potential to be transformed into sacred space. Moreover, this does not constitute a straightforward contest between the State and society, but rather an ongoing and often unspoken process of negotiation, with implicit compromises being made on both sides (Heng 2021, 17). This eventually results in a constant process of regulating and contesting the use of space.

Waghorne, Heng, and Chan’s studies explore either highly public spaces, like cemeteries, or very private settings, such as HDB flats. The HDB void deck embody a combination of both. They serve as multi-purpose areas for weddings, funerals, celebrations, and various personal activities, while also being subject to regulations from the State or town council, which means residents cannot use the space freely.

Case Study: The Cantonese Funeral Ritual in Singapore

This article focuses on a single ritual dazhai (the funeral ritual)[3]—and investigates how the nanfu masters employ the ritual’s powers to subvert the state-assigned profane space into a sacred religious space. The funeral ritual is the core component of a complex set of death rituals in Daoism, reflecting the cosmology of the Cantonese people. Lai (2007), for example, believes that the funeral ritual embodies the ultimate concern of Cantonese Daoism. More specifically, the Cantonese people believe that conducting the ritual allows the soul of the deceased to be reincarnated to a better life and to ensure that the mourners are also safeguarded by their ancestors (Lai 2007, 209–10). To paraphrase Victor Turner (1969, 94–95), the funeral ritual represents a moment of renewal, a moment of cleansing, and an occasion for engaging in a role reversal.

Embodied Sacredness in Cantonese Funerals at HDB Void Decks

HDB estates are characterized by numerous transitory and liminal spaces, many of which have become rich sources of literary engagement and imagination (Cheong 1996, 1–21). In a more general sense, the HDB void decks are spaces designed and regulated by the State and intended for offering the same liveliness and spontaneity that made back lanes so attractive to early HDB settlers.

Void decks integrate features of both public visibility and privacy. When they are not reserved for such specific purposes as funerals or weddings, void decks are communal areas where residents can enjoy their leisure time (Seng 2011, 143–59). However, stringent regulations are enforced to prevent “misbehavior,” such as spitting and littering, to reinforce the notions of state control over these open spaces. Accordingly, all residential properties must abide by the rules and policies set out by the HDB authorities. The dual nature of a void deck provides opportunities for individuals to imbue it with ethnic or religious elements during various occasions. Thus, sacred space is still influenced by state regulations and physical limitations. As noted by Heng (2021, 187), sacred space is not only fluid and flexible but also temporary and reflexive given that it eventually recedes back into the everyday landscape. This, in turn, demonstrates how it is encapsulated within the everyday spaces of life and interwoven into the fabric of everyday life in Singapore.

The deceased’s family must make an application to the relevant authorities—usually the town council or residents’ committee—to carry out a funeral on an HBD void deck. The nanfu masters, however, do not require any official permission for performing their religious functions. According to LifeSG, an online platform established by the Singapore government to help Singaporeans to locate and make use of government services and information, the deceased’s family must obtain a permit from the town council so it can book a date for the funeral (LifeSG, n.d.). There are also regulations that govern the times in which funerary rites can be conducted. In most cases, the funeral must end no later than 10 p.m. Accordingly, most funeral rituals usually begin at 6:30 p.m. and end before 10 p.m.

After obtaining a permit, the next step in creating a sacred space within a HDB void deck is the placement of religious apparatuses. As shown in Figure 2, void deck pillars and tarpaulin sheets are strategically used to create “rooms” where the deceased’s body is placed in the innermost area, and a temporary altar and other offerings are positioned within the partitioned space. In doing so, the nanfu masters successfully separate the state-regulated profane space and the sacred religious space both inside and outside the void deck.

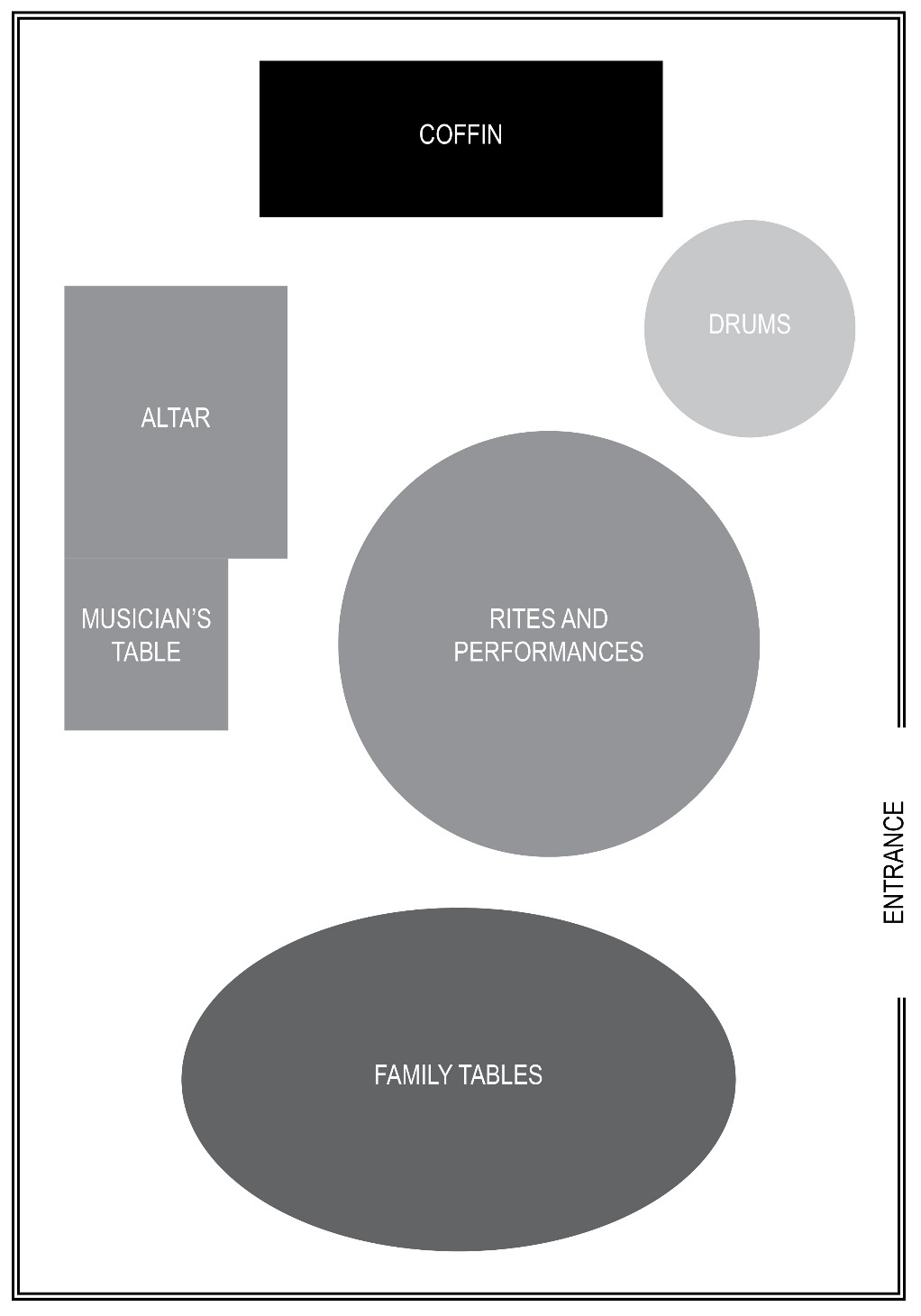

With guidance provided by the nanfu master, the bereaved family help to transform the HDB void deck into a sacred space by constructing elaborate altars, banners, and entrances in and around the deck as shown in Figure 3. Figure 4 presents a void deck funeral floor plan. The deceased’s coffin is placed inside a tent in the innermost part of the deck. A drum is then positioned next to the coffin to facilitate the bereaved family’s burning of paper offerings. In addition, the nanfu masters set up a temporary altar and a prepare a table for the musicians. The middle area of the void deck is used for performing rites, such as the rite of po diyu. By doing so, this communal area is transformed into a sacred religious landscape for funeral rituals.

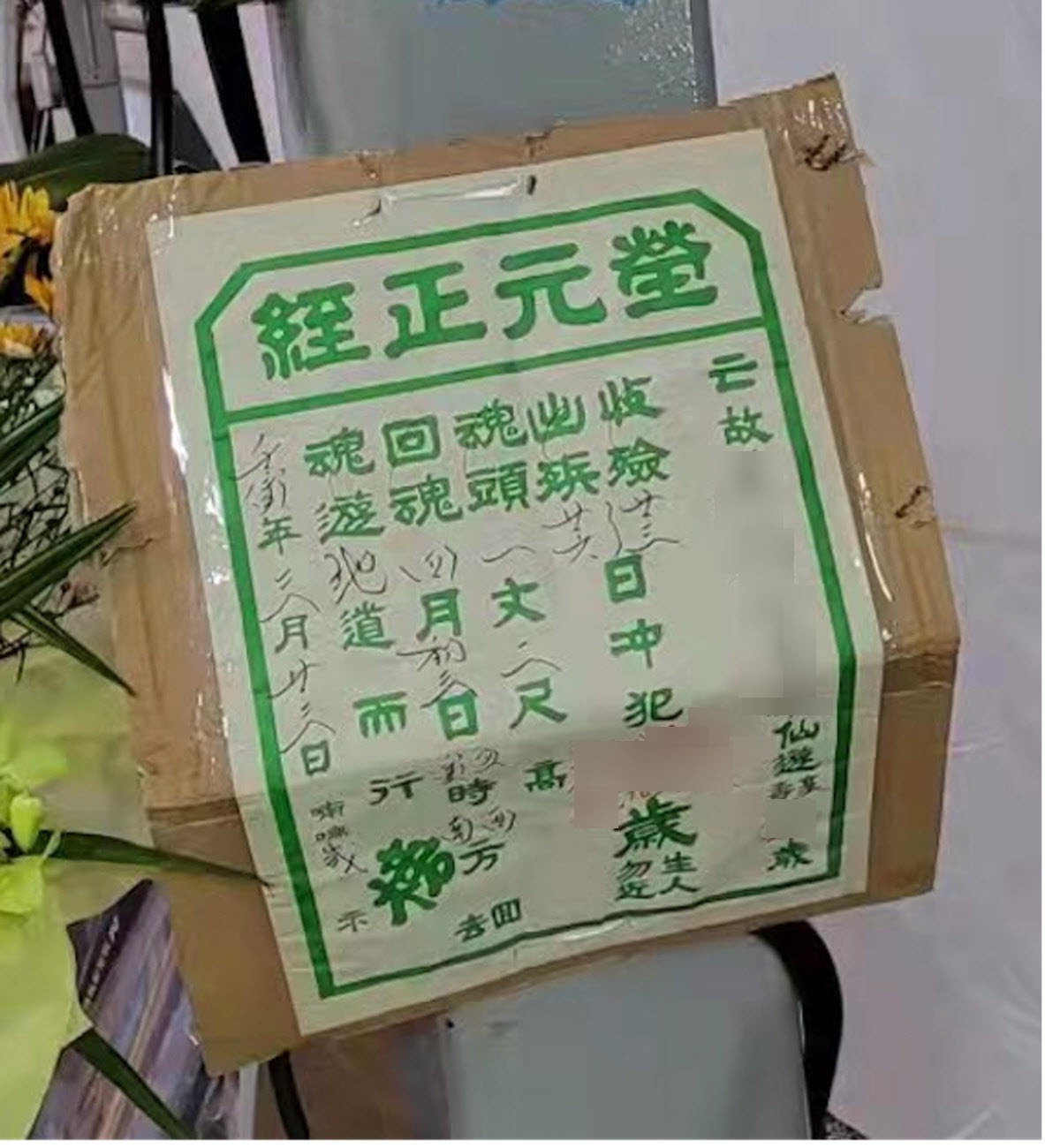

A significant symbolic gesture associated with creating this sacred religious space is the placement of a yellow jing zheng yuan ying (death information notice) at the entrance to the void deck. This notice is provided by the nanfu master and filled in by the deceased’s family (see Figure 5). The notice contains the deceased’s name, age, and even the height of their soul and the date when the it will return home. It also includes important information that bereaved relatives and friends should be aware of, such as those who should not be present when the deceased’s body is brought back to the funeral site and those who should avoid looking at the coffin while the body is transferred to the hearse. This placement of the notice indicates that the communal void deck has now become a private sacred space for the funeral ritual, despite its temporary nature.

Funeral Rituals and the Nanfu Masters

The Cantonese generally hold a conservative view of funerals and consider death as a form of pollution due to their belief that people are vulnerable to the shaqi (killing air) emanating from a corpse. Paradoxically, they still ascribe a great deal of importance to the performance of mortuary rites despite this aversion to death. In this respect, the funeral ritual is significant in that it addresses and manages the pollution of death as well as ensures the elimination of pollution through the refinement of the soul (Watson 2011, 355–60).

The funeral ritual is also significant because its essence draws on symbols of cleansing, healing, and the binding of ancestral ties. In this respect, Lai (2007, 210–12) points out that the Cantonese funeral ritual is imbued with such moral values as filial piety and loyalty. Specially, the soul of the deceased is bound and brought under control so that it can be appropriated by the deceased’s descendants. The major purpose of the funeral ritual is to adapt the soul to its new and complex environment in hell. As noted by Freeman (1971, 118–54), the logic of death in a diasporic society like Singapore accords with a larger sociocultural value system, especially insofar as kinship is concerned.

The funeral ritual must be conducted by professional specialists. According to James Watson’s (2011, 392) observations in rural areas of Hong Kong, a clear stratification and hierarchy exists among funeral specialists, including geomancers, Daoist priests, nuns, and others, based on their relative “exposure” to the death pollution and on the standard of their skills, training, and literacy required to carry out ritual tasks. However, in present-day Singapore, only nanfu masters can be found during a funeral, and they alone act as the ritual’s protagonists.

The funeral ritual cannot begin until the nanfu masters signal the start of the rites. My observations show that there is a chief master who is hired for the funeral by the bereaved family. This chief master, in turn, acts as a coordinator and shares the work with other freelance nanfu masters. The chief master also brings the apparatuses used in the ritual with him.

From observation, there is a clear division of labor among the nanfu masters. The chief master, referred to as zhuke (main master),oversees all the major rites. The other two masters, referred to as laudou (senior priest) and jianzhai (vegetarian meals supervisor), in turn, are in charge of the rites meant to appease the ghosts by serving them food and other sacrifices. In some funerals, two additional masters assist in chanting. The musician employed in the ritual is referred to as jiaoshi (deity summoner) and mainly plays the instrumental prelude and interludes.

As part of their preparations, the nanfu masters set up an altar for the ritual (see Figure 6). The altar is a small table containing a hanging scroll known as shenzhou (The Axis of the Deities). This scroll depicts the sanqing (The Three Pure Ones, the High Daoist Triple Deities), namely yuanshi tianzun (The Celestial Worthy of the Primordial Beginning ), longbao tiansun (The Celestial Worthy of the Numinous Treasure), and daode tianzun (The Celestial Worthy of the Way and Its Virtue ), as well as the shi wan dian (Ten Pictures of the King of Hells). The pictures of the sanqing are hung in place when the priest prepares the altar. Finally, the fruit offerings for the sanqing and all the other apparatuses used in the ritual are also placed on the table.

The assembly of this altar signifies that the nanfu masters have transformed the inherently empty void deck into a sacred space imbued with religious elements. The rituals they conduct are designed to utilize the deities’ exotic powers to fulfill the needs of the ceremony. Once all preparations are complete, the ordinary HDB void deck is transformed into a sacred space.

Funeral Rites

These nanfu masters’ spiritual power extends beyond the altar, dictating and determining the sacredness of spaces within the void deck. By performing such rites as inviting deities to cleanse, consecrate, and secure the space the void deck temporarily assumes a sacred atmosphere. The funeral rituals temporarily replace the state-defined space revealing the conflict between ritual practices and modern infrastructure and regulations and illustrating how spiritual beliefs coexist and intermingle with the mundane in Singapore via religious rituals.

The funeral ritual typically takes place in the evening. At around 6:30 p.m., the nanfu masters put on their hats and robes, and the musician strikes his gong and plays a loud musical accompaniment to signal the beginning of the ritual. The funeral ritual consists of six rites: qingshen (Inviting the Gods), kaijing (Opening Sutra), po diyu (Breaking the Netherworld Gate), wuludeng (Chanting the Lights of the Five Directions), and guo xianqiao (Crossing the Immortal Bridge). On some occasions, guo xianqiao is replaced with another rite known as sanhua (Scattering Flowers).

The first two rites are performed to transform the state-assigned profane void deck into a purified sacred area. The first rite, qingshen, involves the nanfu masters summoning the deities and requesting their protection. This process gradually transforms the void deck into a sacred space filled with the deities’ exotic powers. Chanting the bada Shenzhou (Sutra of the Eight Great Daoist Mantras), the masters perform the second rite exercizing sacred power to further protect the wake. At this stage, the bereaved family follows the masters’ instructions and prepares paper sacrifices for the deities.

The third and fourth rites form the core components of the funeral ritual, illuminating how the Cantonese people construct the concept of a soul. The po diyu rite, is performed next to the coffin to guide the deceased’s soul on its journey through the underworld. To this end, a symbolic “hell” is created (Figure 7) that is made up of nine unfired tiles, corresponding to the nine courts of the underworld through which a soul must pass before reaching the final court where its future will be decided. This rite is mainly performed by one nanfu master, supported by four others. The deceased’s eldest son holds the soul tablet and stands next to the hell while the masters dance around breaking all the tiles in sequence until the soul is rescued.

This rite is important because it reflects the Cantonese people’s belief that an aspect of the soul continues to reside within the deceased’s body while coexisting simultaneously with other aspects in the netherworld and, symbolically, within the hell (Watson 2011, 368–70). The Cantonese not only perceive the deceased’s bones and ashes as the remains of an individual but also consider them to have specific needs and wants. The body is therefore treated as if it is alive and individual regardless of death.

On some occasions, when the bereaved family prefer a smaller-scale ritual, the nanfu masters do not perform the po diyu rite. Instead, they chant wuludeng to guide the deceased’s walk through the underworld. In these cases, the soul is guided by a light to let them know where they are and to help them accept the fact that they have already died.

The last two funeral rites, guo xianqiao and sanhua involve a process of reciprocal gift exchange between the dead and the living. In most of the rituals witnessed by the author, guo xianqiao is the final rite. This rite helps the deceased’s soul cross two paper bridges on its way to the “Pure Land”. The nanfu masters set up two paper bridges, one decorated in gold, and one decorated in silver. The mourners line up on one side of the bridge. The eldest son holds a banner and picks up the deceased’s soul tablet while other family members stand behind him holding joss sticks. The son guides the soul tablet across the two paper bridges according to the nanfu masters’ instructions. The mourners carry the soul tablet between the bridges several times.

Sanhua is only performed in some funeral rituals. In this rite, a collection of flowers and coins is spilled onto the floor while the masters chant the Lingbao tradition’s lingbao sanhua jinke (Golden Register for the Scattering of Flowers). When performed, this rite serves to comfort the mourners and relieve their sorrow. Flowers and coins are essential elements in this rite. The coins are subsequently picked up by the mourners to signify money left to the family of the deceased in the hope that they will be prosperous and lead a better life. This practice reflects the strong bond between ancestors and their descendants among Cantonese people.

By performing these last two rites, the deceased’s descendants successfully offer gifts to their ancestor enabling it to be transformed from a hungry ghost into a benevolent spirit and granting ancestral gifts of luck and well-being in return (Tong 2004, 7–8), demonstrating the reciprocal relationship the Singaporean Cantonese community have with their ancestors.

Finally, the nanfu masters lead the bereaved family to burn all the paper apparatuses in the furnace near the void deck, and by doing so, ending the funeral ritual. The funeral ritual takes approximately three and a half hours to complete.

Although there are limited records on Cantonese funeral rituals in Singapore’s past, Topley’s (2011, 4–11) thorough descriptions from the 1950s provide an exhaustive account of the rites conducted by nanfu masters. She observed the funeral ritual in the funeral parlors at Sago Lane, which was a Cantonese enclave in post-war Singapore.

A comparison of the funeral ritual in contemporary Singapore with that of the 1950s shows that it remains closely modeled on earlier performances, although its duration has decreased by almost eight hours. This is due, among other factors, to the disappearance of certain rites—for example, pou dou gu wan (The Universal Liberation of the Wandering Spirits)—which are absent from present-day fieldwork records. A detailed comparison of the author’s observations with Topley’s 1950s account is provided in Appendix 2.

As Tong and Kong (2010, 36) state, the changes in funeral rituals in modern Singapore reflect new spatial arrangements and constructions of community that can be attributed to urban renewal and the resettlement policies adopted by the Government. In other words, the funeral ritual itself has changed and has become more intense with state regulation acting as an invisible hand that manipulates the rituals in terms of both duration and scope.

Sacred Objects

Sacred spaces are not confined to a specific territory but can, in fact, be remade and reconfigured with sacred objects (Figure 8). The sacred boundary is further extended through the placement of religious paraphernalia. With funerals, this manifests in makeshift arrangements of food, drink, incense sticks and candles set up for the deceased whose presence transforms the landscape from a physical space to a combination of a physical and spiritual space. Ritual supplies and paper offerings reveal how the living interact with the dead it what can be perceived as a mundane manner.

In a funeral, paper offerings symbolize such items as money, clothing, housing, mobile phones, credit cards, and more. When burned, these tangible and embodied items become fragmented and ethereal, transformed into objects for use and consumption by the deceased’s spirit in the spiritual world. The moment of burning marks the complete delivery of gifts and offerings intended for the deceased. The incineration process (Figure 9) allows the bereaved family and friends to visually confirm their family member’s transference from the physical realm to the deceased. The use of these ritual paraphernalia in motion contributes to the making of sacred flowscapes (Heng 2021, 161–62).

Heng (2015, 58–61) labels these objects as “transient aesthetic makers,” describing them as items and actions that support an individual’s comportment and reveal aspects of their ethnic identity. Individual identity thus differs from state identity but is also fleeting and evasive. In this respect, the performance of funeral rituals in HDB void decks temporarily assigns a unique social and religious significance to these physical locations, one which differs from the state’s assigned roles for them. This creates as a baseline for a tension-ridden performance and enactment of identities.

The Manifestation of Cantonese Identity

Despite changes in the duration and format of funeral rites, funeral rituals continue to reflect Cantonese cosmology of souls and the underworld, serving as a distinctive marker of Cantonese identity. As shown above, state-planned ethnic homogenization is temporarily subverted through the rites conducted by nanfu masters and through the presence of ritual paraphernalia.

Since the late 1970s, the Singapore government has promoted Mandarin as the common “mother tongue” for all ethnic Chinese and has banned the use of dialects in radio and television broadcasts. Consequently, the linguistic diversity within the Chinese community has gradually diminished as speech patterns became increasingly homogenized (Clammer 1985, 133–37).

Despite this, language continues to play an important role in expressing self-identity, particularly during religious festivals. Heng (2014, 148; 2015, 57–58) observes that expressions of “Chineseness” remain evident during the rituals of the Hungry Ghost Festival, even amid the hybridization and syncretization of cultural forms over time. During these festivals, state-defined public spaces are temporarily transformed into imagined, ethnicized “second spaces” that reaffirm communal identity.

Chan (2020, 1–13) similarly notes that the getai during the Hungry Ghost Festival provide an opportunity for dialect speakers, particularly those identifying with Hokkien heritage, to express their regional ethnic identification. Likewise, the funeral rituals conducted on a void deck offer an alternative to the State’s planned narrative.

Despite its fleeting temporality, the density and positioning of transient aesthetic markers in the HDB void decks—where they are not normally found—amplify the performativity of Cantonese identities. The funeral ritual is conducted in Cantonese, as are all the conversations between the nanfu master and the deceased’s family. With the assistance of the nanfu masters, the deceased and their family reinforce their ethnicity during these rites and express how they differ from a unified state-imposed identity while preserving the continuity of their unique Cantonese identity.

The liminality of these sacred spaces further highlights the formation of ethnic identity within Singapore’s Cantonese communities. The placement of temporary altars and religious paraphernalia functions as a form of identity performance. The manuscripts chanted by the nanfu masters in vernacular Cantonese language further reveal how individual actors, exercising their cultural agency, subvert homogenized state narratives of “Chineseness” through region-specific cultural practices rooted in their ethnic origins.

The funeral rites performed by the nanfu masters are transient in nature: the altar is dismantled at the end of the ritual as quickly as it is set up. Figure 10 shows the altar disappearing almost immediately to comply with the funeral’s time-limited permit. All the offerings, including the joss paper, the food, the instruments, and even the altar, are present for only a few hours and are always ready to be cleared away. This demonstrates that the funeral ritual is constrained by state power and shows that both the deceased’s family and the ritual specialists acknowledge the limits set by the State.

Despite adhering to the State’s rules and regulations—such as obtaining permits, complying with noise pollution laws, and performing rites within state-approved hours—these occasions retain their Cantonese affiliation both temporally (before 10 p.m.) and spatially (within HDB void decks). The funerals in the HDB void decks demonstrate the intersections and conflicts between state power, Cantonese identities, and even the deceased’s spirit. This further reveals the transient and active layering of spiritual imagination over planned spaces. The HDB void deck funeral ritual shows how individuals manipulate temporary spaces to reveal their dialectical identity against a background of scarcity, regulation, and restriction in Singapore.

Conclusion

The case study presented in this article reveals that religious rituals in contemporary Singapore are shaped by historical junctures and are imbued with diverse cultural meanings and fields of power. The funeral ritual, which aims to dispel misfortune and bring peace and prosperity to the living, is situated within the context of competing narratives involving the use of space, the performance of rites, state regulations, and even dialectical identity. This case study demonstrates that the very concept of space, often taken for granted and perceived as neutral, can be reimagined, negotiated, and constructed with nuanced meanings.

The funeral ritual described illustrates how state-defined profane space is transformed into a sacred religious space by the rituals performed by nanfu masters. The funeral ritual serves not only as a medium of religious expression but also as a means of shaping and structuring the relationship between human agency and the socio-political environment. Contemporary Singaporean social life, marked by humanist flux, can be captured by stressing religious practices and processes.

While space in Singapore is tightly managed to serve secular goals and promote a homogeneous Chineseness over ethnic heterogeneity, it is not rigid and is often challenged during religious events. The funeral rituals performed by the nanfu masters in the HDB void decks epitomize the interaction and conflicts between state, spirit, landscape, and Cantonese identity. These rituals project local Cantonese identities and demonstrate how religious activities transform state-assigned spaces into ritual sensorial zones.

The funeral ritual tradition has subtly adjusted to its new circumstances and nanfu masters remain in demand. While family connections are no longer essential for recruiting nanfu masters, the Cantonese dialectical identity remains significant. Despite modernization, funeral rituals remain common and are still considered a necessity.

Acknowledgments

The research and writing of this article were generously supported by the project Infrastructures of Faith: Religious Mobilities on the Belt and Road (BRINFAITH) at the Asian Religious Connections research cluster of the HKIHSS, University of Hong Kong, and by the Israel Science Foundation Breakthrough Research Grant no. 2717/22, Environment and Religion in China.

_rite._photo_by_h.jpeg)

_rite._photo_by_h.jpeg)