Since the Imperial era, arranging a proper ground burial for the dead in a timely fashion has been essential for the Confucian funeral ceremonies intended to achieve rutu weian (everlasting serenity) (Suh 2019; Tu 2022). Sweeping family graves and making sacrifices to ancestors are thought to bring auspiciousness to the descendants for generations to come (Sinn 2013; Kipnis 2021; C.-C. Choi 2020). This reciprocal relationship with the deceased underscores the centrality of shared ancestral estates set aside to support ritual observances and grave conservation in China’s lineage society (Faure 2007; Feng 2009; Kipnis 2021, 50; Lin 2013). In the transnationally connected coastal China, emigration to Southeast Asia has been part of a family-based strategy of wealth accumulation, and the ancestral graves embody the desire of huaqiao (overseas Chinese) to return home to be buried among their kinfolks (Chan 2018). Such unbreakable bonds have manifested in repatriating emigrants’ remains from North America to the Pearl River Delta through Hong Kong since the mid-nineteenth century (Sinn 2013, 265–96).

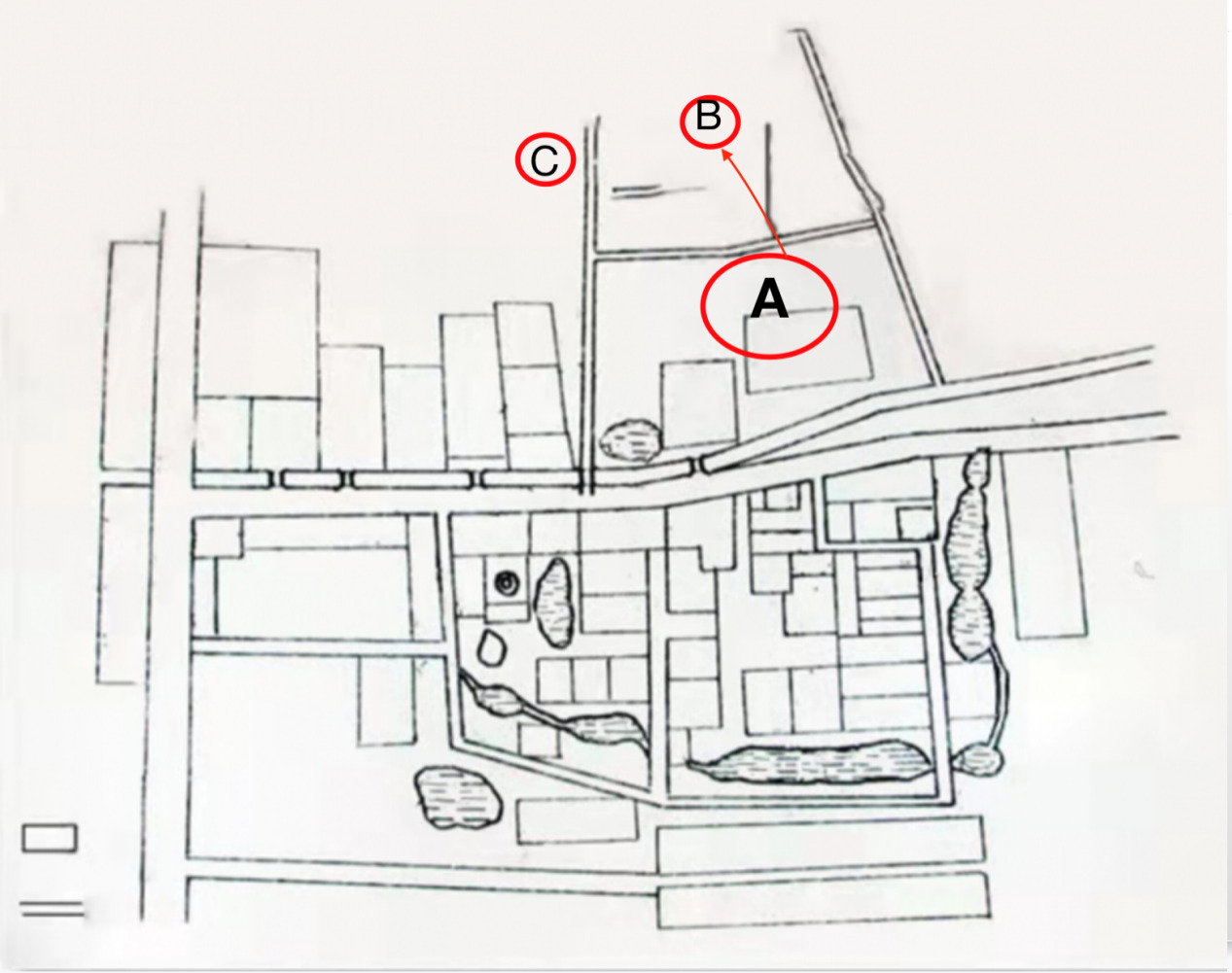

When the early Communist measures to convert gravesites into arable land clashed with the transnational experience of emigrants, it caused bitterness in areas with high concentrations of huaqiao and guiqiao (returnees). As the emigrant graves were imbued with deep social meaning, the coercive policy of grave demolition destroyed the cultural appeal of “ancestral home” for emigrants and drove the latter to settle in Southeast Asia permanently (Lim 2019). This article investigates the implementation and effects of grave relocation in Guangdong Province’s Chaoshan area, a colloquial abbreviation of Chaozhou and Shantou. It draws on declassified county-level archival documents and field research data to discuss the social reception of grave removals in the qiaoxiang (emigrant communities) of Hougou (Rear Ditch) and Dawu (Big Wu) during the 1950s (Figure 1). These communities were chosen because of the easy accessibility for fieldwork. Hougou is a single-surname settlement located next to a branch of the Han River north of Chenghai City.[1] The Xu clansmen, who had traveled to Siam (today’s Thailand) for work since the late Qing period, founded the Thailand Hougou Xushi Lianyihui (Hougou Xu Clan Association) in Bangkok to stay in contact with relatives at home through letters and remittances. Dawu is a single-lineage community, situated north of Shantou along the Han River, and the Wu lineage members migrated to British Malaya around the same period.[2] In addition to establishing the Singapore Shennong Association, the Wus founded a charity hall named the Seu Teck Sean Tong Yiang Sin Sia (Xiude Shantang Yangxinshe) to express allegiance to Grand Master Song Dafeng, their ancestral village deity. Even though China’s socialist transformation severed these cross-border linkages and led to the State’s takeover of overseas Chinese-dominated piju (remittance offices) in the 1960s and 1970s, the less restrictive environment of the 1980s enabled the Xus and Wus to reclaim cultural links to their native homelands. Generational changes have reduced intimate contact between the Xu clan association in Bangkok and Hougou in the early twenty-first century. Still, the Wu charity hall in Singapore maintains a close connection with Dawu. Whether secular or faith-based, these mutual aid associations have organized emigrants’ daily business routines, friendships, and religious life. Such transnational ties have expanded from their initial mutual conduits for remittances into an invisible network of resources for the upkeep of emigrant graves (Benton and Liu 2018).

Beginning with a methodological discussion of archival research and fieldwork, this article reconstructs the social settings of emigrant communities in Hougou and Dawu before the pingfen (grave-flattening) campaign in the 1950s.[3] Then it identifies the diverse patterns in which emigrants interacted with a centralizing state determined to turn gravesites into farmlands, and in which they adapted to the official policy by aligning their ancestral attachment with the utilitarian agenda of rural cadres. Here, the politically loaded term huaqiao needs to be clarified. Wang Gungwu traces its intellectual genealogy to the “assimilationist or integrationist policies of the new nation-states” across Southeast Asia (G. Wang 1994, 52). The voluntary act of sojourning, like that of migrating and settling down, became polarized when twentieth-century nation-states ruled over large numbers of aliens and mobilized them for political purposes. G. Wang (1994) points out that the mid-nineteenth century witnessed a change in the pattern of Chinese migration to Southeast Asia from that of huashang (Chinese sojourning merchants) to that of huagong (Chinese laborers). Huagong quickly outnumbered the huashang at trading ports. Whether residing abroad permanently or returning home was subject to the living conditions of host societies. The early twentieth-century Chinese revolutionary movements organized huashang and huagong to support the motherland, thereby giving rise to the eloquent term huaqiao (G. Wang 1994, 54–55). After 1949, huaqiao were compelled to choose between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the exiled Republic of China (RC) in Taiwan. Thus, Wang prefers a neutral term “Chinese overseas” when describing people of Chinese descent outside the PRC and Taiwan (G. Wang 1993, 2017). Leo Suryadinata considers decolonization in Southeast Asia and uses the label “ethnic Chinese” for Chinese residents after 1949 (Suryadinata 2007, 1–3, 29–30). Since many Chaoshan emigrants were members of these huashang and huagong communities, this study adopts the term “overseas Chinese” as a generic category without distinguishing whether they hold the PRC or RC nationality.

Reflections on Archival and Ethnographic Research

A few words must be said about the selection of archival and ethnohistorical data for analysis. Accessing the catalogs of Chinese municipal archives is relatively straightforward when working with primary sources. The archival catalogs broadly divide the collections of lishi ziliao (historical materials) into the pre- and post-1949 era. Any materials that were produced before the Communist Revolution of 1949, known as the period of pre-Liberation, are usually open for research. Official records after 1949 can be problematic because the documents might reflect badly on some of the Maoist policies in rural areas. The authors had no trouble accessing the municipal documents on overseas Chinese affairs during the 1950s and 1960s but the political nature of these reports presents an interpretative challenge. Written in the orthodox Maoist discourse and intended for Communist Party officials in charge of overseas Chinese affairs, the materials often referred to emigrant households as “reactionaries” who showed little ideological commitment to the socialist motherland. This characterization is just one example of the biases that color the official evidence.

Another methodological challenge lies in assessing the representativeness of the reported grave disputes. In surveying the removal of foreign and Chinese cemeteries in Shanghai, Christian Henriot (2019) acknowledges that “the silence of the archives or even just silence” over “the displacement of the vast majority of burial grounds” is the major challenge. The same problem can be said of dismantling lineage cemeteries and hillside graves in Chaoshan. The grave disputes documented by local officials only represent the tip of an iceberg, pointing to “a small sample of the continuous and sub-rosa process that pushed burial grounds further away from the urban area or simply erased them” (Henriot 2019). Nonetheless, the municipal and county-level archives contain valuable information about the difficulty of enforcing such compliance in emigrant communities. Founded in 1954, the Bureau of Overseas Chinese Affairs (Qiaowu Shiwu Ju) addressed emigrants’ grievances and provided the initial contact for huaqiao and guiqiao to seek official assistance in disputes. Many huaqiao could not comprehend that the communization of village society in the Dayuejin (Great Leap Forward) in 1958 completely undermined their interests. In Hougou, one informant recalled a tragedy in which a landlord from an emigrant family drowned himself after he publicly refused to surrender his rice and grain stocks.[4] Responding to the adverse effects of the land reform on huaqiao families, the institutionalization of guiqiao as an administrative category and the provision of youdai (preferential treatment) represented “the most elaborate state initiative” to co-opt the overseas Chinese (Chan 2018, 149). The Communist bureaucratic reports on overseas Chinese affairs document guiqiao complaints about the destruction of ancestral graves, their negotiations with village cadres, and the range of coping strategies deployed to circumvent the State’s stringent measures. Petitioning the municipal officials was a major step to holding the local Communist Party/State accountable to overseas Chinese. The records reveal a discrepancy between the PRC’s developmental agenda and guiqiao concerns, which led to the State’s policy adjustment in the mid-1950s. Missing in the reports are the subtle relationships that had shaped the encounters between guiqiao and rural cadres in Chaoshan. Nor is there any data on guiqiao feelings of pain and anxiety caused by the coercive removal of their ancestral tombs. One way to overcome the inherent biases of the official documents is to gather relevant field data from Hougou and Dawu. The authors conducted annual fieldwork in Chaoshan from 2012 to 2023, observing specific festivals in guiqiao communities and maintaining contact with participants. Hui Wang has written on Hougou temple processions that took place on the sixth to the fourteenth day of the Lunar New Year, and the centennial return of the statue of patron deity, Grand Master Song Dafeng, from Singapore to Dawu in 2014 (Wang H. 2013, 2016). Joseph Tse-Hei Lee builds on his ancestral ties in Chaoshan to investigate the changing funerary customs among local Christians, thereby contributing to this project’s depth and breadth (Lee 2003a; Chow and Lee 2021).

Several conditions in China make fieldwork challenging. First is the high level of literacy. There are numerous written materials in every locality: genealogies, family correspondence, photos, account books, land deeds, etc. After many years of fieldwork in the New Territories of Hong Kong and the Pearl River Delta, David Faure (1987, 14–5) urges anthropologists and historians to collect and consult these written materials. The purpose is to move beyond our preconceived assumptions and see the local society from the vantage point of villagers (Faure 2020, 18). Despite many decades of turmoil in twentieth-century China, Chaoshan huaqiao often have private records, all of which are seldom found in the Chinese official archives. Another element concerns China’s centralized bureaucracy. Researchers without personal connections may need to go through the official hierarchies in preparation for fieldwork, that is, to obtain approval from government officials before visiting villages. Outsiders must claim some identities and renounce others at different moments of the field research. During multiple trips, the most crucial task for the authors was to establish their credibility as trustworthy scholars. In rural Chaoshan, the idea of an individual not being part of a community or being alone is inconceivable.

The authors are in a unique situation of being researchers with deep interest in the history and local culture of Chaoshan. Their relationship with village officials and huaqiao families highlighted the comparative advantages and disadvantages of their positionality. They are semi-insiders given their academic agendas and outsiders due to their upbringing. These multiple identities were derived from unique circumstances and the participants’ perceptions. When they were aware of these identities, they employed them as best as they could to gain trust from participants. They visited huaqiao families, attended many ceremonial events, and documented the changing settlement areas and kinship ties in Dawu and Hougou. They used participant observation as their primary research approach. By attending ritual ceremonies in honor of the deceased, they came to appreciate the centrality of ancestral veneration and temple activities in huaqiao households. Welcoming the authors as guests, the participants discussed the history of their family connection with Southeast Asia, their memory of grave demolition during the Maoist period, and their resolve to rebuild ancestral tombs in recent decades. Despite their powerlessness, they challenged the sanitized official history of grave removal, reminding readers of the value of oral history and remembrance for ethnographic research (Jing 1996). Upon finishing the fieldwork, they used WeChat and QQ social media platforms to ask the participants further information.

The field data answers questions not addressed in the official sources and permits an in-depth exploration of the cultural, social, and religious factors shaping burial practices in huaqiao communities. Due to some participants’ reluctance to discuss topics related to death management, the authors adopted observation as a methodology to document the impact of Maoist funeral reform policies on burial practices in local households. Whenever possible, they visited the Chaozhou Municipal Archives to collect local government documents and newspaper articles to supplement the field research. The authors also visited thirty huaqiao families in Hougou and interviewed ten of these households to collect genealogical data. In Dawu, the authors interviewed more than ten families. These conversations highlight the participants’ “hidden transcripts” regarding their less visible forms of resistance against the top-down policy of grave removal. As much as the authors will try to remain balanced in their analysis, they cannot hide their genuine concern and respect for those villagers who had become traumatized and critical of such a coercive policy. Thus, insights gained from archival and field research provide a variety of viewpoints to counterbalance official narratives.

The Landscape of Hougou and Dawu

Hougou and Dawu were chosen for their representativeness, as both have long-standing huaqiao connections to Southeast Asia. The continuous resource and information exchanges were, and still are, connected with the preservation of ancestral graves in huaqiao households. Huaqiao responses to the Maoist State’s grave removal campaign shed light on the changing identity and lifestyles in their communities. Hougou has a population of 4,000, and Dawu has 2,000 residents. They are single-lineage settlements and consist of landholders, craftsmen, merchants, and farmers. Dawu compiled a comprehensive genealogy of the Wu lineage in 1996 to solidify group cohesion, whereas the Xu lineage in Hougou is not known to have produced a genealogy after 1949. Even though these lineages are divided into rival segments, they trace what they perceive as their common descent for more than five generations. They are largely territorial communities and hold shared properties to support various local projects (Freedman 1958, 1966). Both communities feature several temples as focal points for popular religious practices. Before 1949, these settlements held lavish temple processions or deity parades to demonstrate strength and unity within their territorial boundaries, and they discontinued such practices during the Maoist era (1949–76). Hougou revived the religious processions in the 1980s thanks to the contributions of their overseas relatives in Thailand, and Dawu reopened the temple to accommodate the Wus from Singapore and Malaysia. Known for its participation in the Communist revolutionary activities during the 1920s, Hougou publicized this revolutionary heritage to gain government resources after the 1980s. Renowned for the craft of clay figurines, Dawu seized new commercial opportunities to increase wealth and prosperity. Below is a comparison of the socioeconomic profile of these two settlements (Table 1).

The analysis of Hougou and Dawu not only complements existing research on death governance in modern China but also sheds light on huaqiao social reception of grave dismantling and its adverse effects on their attachment to Chaoshan. Historians have applied the geographical concept of “deathscape” to study the interplay between the Chinese death commemoration practices and the State’s measures to erase traditional cemeteries and institutionalize cremation as the preferable form of handling the deceased. Thomas Mullaney (2019) and his team of experts have mapped the effects of grave demolition and burial reform in townships across the Lower Yangtze region and Western China since the late Qing. Recent anthropological literature on death governance has shown that the end-of-life commemoration in Shanghai and Shenzhen embodies accumulated cultural conventions, and modern funeral practices often reframe socialist, religious, and relational understanding of self and families (Guo and Herrmann-Pillath 2023; H.-M. L. Liu 2023). Despite the findings on the temporal and spatial variations of death commemorations in China’s hinterlands and metropolises, researchers overlook the migratory linkages that prompted Communist authorities to issue preferential treatment for huaqiao households (Kuhn 2008, 25). Even though the Communists’ removal of all cemeteries to create room for collectivization conflicted with the outward-looking orientation of Chaoshan huaqiao, the latter exercised their limited and vulnerable agency against such coercive measures. Thus, how the huaqiao perceived their deceased relatives as being mistreated by rural cadres, how they utilized their transnational resources to petition the local state, and how the county authorities handled huaqiao gravesites differently should throw light on Shelly Chan’s characterization of huaqiao as being shaped by various diasporic moments instead of being a singular embodiment of dispersed groupings (Chan 2018). When Chaoshan was forcibly transformed from a fluid mobile environment into a state-centric agrarian society, the disputes over huaqiao graves give us a unique lens through which to contextualize specific diasporic experiences fractured by external political intervention.

Flattening Scattered Graves for Collectivization

Effective management of land resources is vital to state building, and this is particularly true for the early years of the PRC. Claiming that scattered graves occupied too much land and obstructed mechanized farming, the Communist rulers followed in the footsteps of the Republican modernizers to target old graves and advocate cremation against “feudal” earthly burials (Y. Wang 2012). From the 1950s onward, the massive demolition of old graves was part of the drastic measures to improve agriculture under the agenda of planning and strengthening socialist control over grain production (Ash 2021). The imposition of planned farming and the collectivization of rural life guaranteed labor efficiency and generated productivity. Responding to Mao Zedong’s call for accelerated collectivization on July 31, 1955, the initial timetable of gradual transition toward socialism gave way to state-enforced coercion, forcing peasants into socialist collectives. In two years, the Dayuejin integrated peasants into the organizational infrastructure of People’s Communes. By 1958, the system was entirely in place, with more than 260,000 communes across the country supervising as many as 120 million peasants in agricultural production. Take Chao’an County as an example, where the communes were institutionalized in September 1958 with communal canteens, nurseries, and homes for older people. The goal was to mobilize peasants to plow the land, build water conservation facilities, fill ditches, and convert burial grounds into farmland (Chaozhou Wenshi Ziliao Bianjizu 2006, 26:19–20).

Accelerating grave relocation was thought to improve resource management. The 1950s funeral reform replaced Confucian burial rituals with cremation and work unit-led memorial meetings (Guangzhou Difangzhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui 2000, 599). In 1956, the Central Government called on the public to replace ground burial with cremation (Diao 2014, 289). Promoting an atheistic attitude toward death, the Maoist State gave the green light to remove scattered graves for development (Nongyebu Tudi Liyong Ju 1958, 130; Tu 2022, 510–11). The official rationale was that grave relocation aimed to secure more farmland and improve food security. Unlike the Confucian gentry who ensured proper funeral norms and provided the poor with affordable burial plots, the Communists were determined to maximize land resources and eliminate the “feudal superstitious” customs such as geomancy and wasteful sacrificial rituals (Nongyebu Tudi Liyong Ju 1958, 130; Lau 2013; M. Choi 2017, 162).

Whereas individual, family, and lineage graves were imbued with the symbolic meaning of the widespread belief in an afterlife, the Communist rulers regarded, and still see, the irregularly scattered gravesites as untapped resources. The collectivization campaign greatly impacted huaqiao communities. A traditional stronghold of the Zhuang lineage, the Guolong Production Brigade in Puning County removed more than a thousand old graves, with remains and bones, including huaqiao graves (Zhuang 2015, 19). Puning County flattened many graves to free 270,000 mu (Chinese acre) of land for collective farming (Puning Difangzhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui 1995, 131). Even many graves of Communist revolutionary martyrs were destroyed in the process, and the county authorities had to rebury the martyrs’ remains in a new shrine in 1959 (Puning Difangzhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui 1995, 22).

Beneath the rhetorical discourse of collectivization was a thorough rejection of Chinese cosmological concern. According to Luo Tian, General Party Secretary of the Communist Party in Shantou, “To implement the great campaign of tudi da pingzheng (flattening the land) is to change the backwardness of land use practices fundamentally. This campaign is not just a war on nature but also an ideological revolution against geomancy and feudal superstitions” (Luo 1958). Luo praised Guanshan and Qipan for their effective techniques to flatten graves in lowlands and highlands. The Guanshan Commune allegedly developed five methods to transform 642 abandoned burial grounds and 1,738 graves into cultivated land: lowering the high piles and filling in the low-lying areas after grave removal to make the sites arable; distinguishing various types of surface soil and subsoil in burial sites and applying miscellaneous fertilizers to improve soil quality; digging ditches to rectify drainage issues; straightening country lanes to avoid detours; and flattening uneven grounds and turning wastelands into paddy fields by modifying ridges and combining scattered fields. For example, Weicuo (Wei Settlement), a single-surname village incorporated into the Guanshan Commune, owned more than 100 graves on more than ninety mu (Chinese acres) of land, equivalent to 30 percent of Guanshan’s territory. As the commune demolished the graves of Weicuo, it constructed a public cemetery for reburial on a sandy slope (Nongyebu Tudi Liyong Ju 1958, 131, 139-40). Evidently, “the individual aspirations of having a good afterlife—by taking up a piece of land—are at odds with the State agenda to promote cremation that would save land and resources and further benefit the wealth of the nation” (Suh 2019, 2). The deceased in Weicuo had no chance of safeguarding their resting places in an acute competition with the atheist State.

Another success story was that of Qipan, where the commune developed four practical ways to remove hilly graves: digging pools and ditches to raise the field ridges; improving drainage and water storage in surface soil and subsoil; digging the ground deeper and applying new soil and miscellaneous fertilizers to strengthen soil fertility after moving the graves; and building roads in hilly terrain to support cultivation and productivity (Nongyebu Tudi Liyong Ju 1958, 131; Luo 1958). The Qipan Commune assigned workers to put up small red flags on the gravesites. When people failed to remove their graves, workers exhumed remains and flattened the structures. The work was so labor intensive that two adults could only remove three to four graves daily (Chao’an Wenshi Weiyuanhui 2008, 48–49).

In late Imperial China, funeral experts were hired to ensure the auspicious timing for exhumation, a ceremony designed to purify the dead and connect the soul of the newly deceased with its ancestors (Watson 1988, 109–34). During the late 1950s, the cadres in Guanshan and Qipan unlikely consulted any fengshui masters who had already been incorporated into the communes. As one writer recalled, “On the buses, at the stations and farmhouses, on the roadside, just about everywhere you go, you hear people talking about relocating graves and digging up what they see” (Qin 2007, 390). Workers jokingly referred to the “grave removal” campaign as that of chelunhua (wheelization), converting the coffin planks into wheels (Qin 2007, 392). Workers liked to cut wooden cartwheels out of the materials because the coffin planks were made of fine wood. In 1958, more than one million graves were flattened nationwide, and over two million skeletons were relocated to hillside cemeteries. The dead were forced to “join the communes” like the living (Nongyebu Tudi Liyong Ju 1958, 132).

Underlying the grave demolition was a profound ideological campaign to eradicate the traditional belief in deities. Even when the late Qing and Republican governments targeted community temple estates and repurposed religious properties for education, they did not invalidate any political and social interests outside those defined by the State. By comparison, the Maoist State imposed a secular-utilitarian worldview over the cosmology rooted in Buddhism, Taoism, and popular religions. Its top-down rural campaigns demanded absolute compliance from peasants and preempted peasant efforts to use the kinship, lineage, and temple networks for resistance. Inflammatory rhetoric against remnants of traditional culture further weakened the ritual service economy (X. Wang 2020, 41–6; Zweig 1989, 154). “The ancestral graves once thought to be sacred for thousands of years, are now demolished by the masses. Gone are the ancestral tablets, together with the statues of the Chenghuang (City God), the Leishen or Leigong (God of Thunder), the Fude (God of Fortune and Virtue) and the Tianhou (Heavenly Empress)” (Nongyebu Tudi Liyong Ju 1958, 133). The socialist state-builders condemned what they perceived to be wasteful and fruitless funeral rituals. In 1958, Raoping County proudly announced to have reduced residents’ ritual expenses during the Lunar New Year celebration (Nongyebu Tudi Liyong Ju 1958, 134).

However, the rapidity of collectivization and the pressure imposed on huaqiao sowed the seeds of discontent. In May 1959, the Department for Letters and Visits (Xinfang Ju), commonly called the Petition Office, assessed the threat of instability posed by the arbitrary demolition of family graves in an internal report to Zhou Enlai and Xi Zhongxun in Beijing. One common problem was that of flattening remote gravesites ill-suited for farming, the tombs of revolutionary martyrs, and the Tibetan Buddhist and Uyghur Muslim cemeteries. Equally problematic was the cadres’ disregard for the feelings of affected families when the communes recycled the wood and stone coffins for construction. Even more troublesome were the looting of valuable burial items and the use of bones as fertilizers (Diao 2014, 287). In Guxi (Ancient Stream), Chaoyang County, the village cadres, who were temple worshippers of the Yao lineage, ordered the Baptist and Catholic teenagers of the Li lineage to demolish scattered tombs and to collect the bones and remains to be made into fertilizers. The cadres assumed that the Christians would not fear the danger of offending the ancestral spirits and mountain deities.[5] A Hougou resident admitted being involved in destroying old graves as a young worker during the 1950s. He was torn between his duty to the village authorities and his feelings for relatives. In the end, political considerations took precedence over sympathy for fellow lineage members. Perceiving the act as a performance of revolutionary fervor and a show of allegiance to the socialist authorities, he and other demolition workers placed red Communist flags on the gravesites. They bought a statue of Mao Zedong to warn off harmful spirits. While digging the graves, they shouted, “Long Live Chairman Mao! Long Live the Communist Party! This is what the top leaders want!” These trivial remarks resonated with what James C. Scott (1985, 35) calls the creation of “partly autonomous and resistance subcultures.” Though being forced to implement the policy of grave demolition, the workers mocked the State’s atheistic ideology and appropriated the Communist symbols for spiritual protection against vengeful spirits. This resident soon rose to be a village cadre and survived the Cultural Revolution. In the late 1970s, he used his official position to hold a lavish funeral for his aunt.[6] The Wus also participated in the local grave demolition, but they were less forthcoming to share their stories. They simply used the defense of superior orders to ease their guilt.[7]

It is worth noting that the grave removal campaign coincided with the banning of what the State labeled “reactionary secret societies.” This process dismantled all charitable and religious organizations that provided burial assistance for the poor. Yet, old customs never died. In Hougou, the Tenglong Ancient Temple enshrined seventeen deities. Troubled by the official order to demolish this temple in the early 1950s, local inhabitants avoided overt collective action and employed a less obvious form of resistance. They buried the seventeen deities’ statues to save them from destruction. The Dawu huaqiao in Singapore used the charity hall to continue the funerary customs in honor of their deceased and the deities. These acts of ritual defiance not only preserved their ancestral heritage but also circumscribed the hostile state policies in Chaoshan. To sum up, the sudden flattening of graves affected the rural death space on three levels. The first change was the creation of intervillage cemeteries to accommodate the demolished graves. Hougou designated a new cemetery on the river embankment south of the village and named it Wanrenmu (Ten-Thousand Tomb). Dawu set up the first public cemetery on forty mu of land, called Renjiabu (Someone Else’s Cemetery), to house the relocated graves in the 1950s. In 1974, Dawu moved the cemetery to a smaller site, occupying four mu of land, and built a cinerarium nearby (Figure 2). The second transformation was the proliferation of hillside graveyards. Hougou relocated some huaqiao ancestral graves to the Lotus Mountain Range, and Dawu and neighboring villages moved their old graves to the Sangpu Mountain, near today’s Shantou University. The third change was the expansion of columbarium burials for huaqiao and guiqiao. In 1957, the Chenghai County government assisted its subordinates in Zhangdong to build a public cemetery, housing 416 guiqiao graves in Zhanglin, a famous emigrant town (Chenghai Xian Qiaowu Bangongshi 1987, 116).

Frequent Occurrences of Grave Disputes

In emigrant communities, the outbreaks of grave disputes were entwined with their relationships with rural cadres. When the concerns of emigrant households and cadres coincided, compromise was possible. When their interests collided or when political pressures were too strong, rural cadres dismissed huaqiao complaints and acted according to their own or the State’s demands (Zweig 1989, 152). A closer reading of the archival materials reveals three types of grave disputes. The first concerned the official ban on burials near water conservation facilities to avoid groundwater contamination. On December 19, 1950, the Central Government issued a nationwide policy prohibiting home construction, ground burials, cattle grazing, and crop plantation on seawall embankments. Still, it permitted county authorities to evaluate the potential risk posed by existing houses and graves to the new water conservation facilities (Zhongguo Tudi Gaige Bianjibu 1988, 702). The second type of dispute arose from removing graves for road construction because of the widespread fear of the disruption of fengshui. In May 1956, the Ma lineage members opposed an official plan to clear over two hundred ancestral graves for a highway to the forest in Jianpu in Chaoyang County. The Ma wrote to their relatives in Thailand and petitioned the county officials, who eventually modified the construction plan to avoid antagonizing the Ma lineage. The third concerned the legal status of old burial grounds and the disputes over the relocation of bodies and bones. From 1955 to 1956, there were eleven such cases in Tiandong, Chao’an County, where the tombstones and temple steles were used for pavement construction and where the damaged graves repaired by huaqiao were destroyed (Diyijie Quanguo Renmin Daibiao Dahui Disanci Huiyi Minshuchu 1956, 1:206–7). This was true in Hougou, where tombstones were taken to pave village roads.[8] By comparison, the Chaoyang County authorities were more willing than those in Chao’an to accommodate huaqiao complaints.

In Chaoshan and elsewhere, emigrant graves were imbued with significant personal memories and social meaning. When huaqiao became successful abroad, they continued to support the upkeep of graves through regular remittances. These resources made the mishandling of emigrant graves a severe issue for the Socialist Government eager to win the hearts and minds of the diaspora. Though permitted to use their remittances on “superstitious” customs, huaqiao were shocked to see the desecration of their graves. In 1956, in Shihu, Chao’an County, the cadres purposefully removed the tombs of returnee Chen Jincai’s parents, outraging Chen and his relatives (Chaozhou Shi Dang’an Ju 1956b). In 1956, the Chaozhou municipal officials received a petition to stop the desecration of emigrant graves, but the problem worsened in the hinterlands. Chao’an had three petitions in 1956 and six written complaints in 1958 (Chaozhou Shi Dang’an Ju 1958). The municipal authorities intervened and publicized the provincial directives on protecting overseas Chinese ancestral graves. Zhu Zhijuan of Guihu Township was distressed when intrusive neighbors demolished her family grave. The county officials sympathized with Zhu and instructed the wrongdoers to repair the damaged grave after harvest (Chaozhou Shi Dang’an Ju 1957).

The grave disputes were sometimes fraught with xiedou (traditional intervillage feuds) (Lee 2003b). A notorious case occurred in Wenli, a multi-lineage emigrant village dominated by the Yangcuo (Yang Settlement), fourteen kilometers south from Dawu. In the 1920s, Yang Jinghao returned from Singapore to build an elementary school. Yang Zuanwen, a leading figure of the Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan [Association of Chaozhou’s Eight Counties] in Singapore—an organization composed of huaqiao from eight Chaozhou-speaking counties—built a second school in Wenli (Chao’an Wenshi Weiyuanhui 1996, 125). These two resourceful Yangs arranged the return of deceased huaqiao corpses and bones from Singapore to Wenli. They also constructed a burial site in a neighboring village of Longtou to keep hundreds of the remains from Wenli. No evidence is given about the compensation provided by the Yangs to Longtou. When the Longtou Commune took over the burial ground and banned the Yangs from sweeping the graves in 1954, disputes broke out. First, the Yangs of Wenli herded cattle to destroy the orchids owned by the Longtou villagers, who retaliated by cutting off the oxtails. Some Yang lineage members stole guavas in Longtou, and the orchid owners desecrated the Yangs’ graves. The escalating conflicts alarmed older people in Wenli, who could not visit and repair the damaged graves. Despite the county officials’ mediation, the Longtou cadres refused to back down, and the problem dragged on for two years. Acknowledging the Yangs’ grievances, in 1956, the Chao’an County officials stepped in and issued the following directives: that the Longtou villagers remove the fruit trees planted on the Yangs’ burial site, stop seizing and converting the Yangs’ graves to arable land, allow the Yangs to visit, repair, and rebuild their ancestral graves, and punish the wrongdoers (Chaozhou Shi Dang’an Ju 1956c). When the Longtou cadres sided with their relatives against the Yangs, the Yangs weaponized their preferential status and petitioned the officials. In this deeply politicized climate, these grave disputes reflected the vulnerability of emigrant families. Many huaqiao resided abroad and could not protect their elderly parents and left-behind spouses. When the aggressive rural cadres intimidated these helpless households and seized their graves in the name of advancing socialism, the county officials found it hard to mediate the situation. Even though the Chinese State wanted to treat the huaqiao favorably, it did not always have its way.

Addressing Huaqiao Fears of Grave Destruction

Recognizing the historical ties of overseas Chinese with the Nationalists and the importance of remittances, the Maoist State strove to co-opt Chinese settlers in Southeast Asia into the service of its political priorities, perceiving the wellbeing of emigrant communities as a strategic and economic issue. In 1956, the third secretary of Chao’an County acknowledged the seriousness of disputes over emigrant graves: “This issue requires special attention and cannot be taken lightly” (Chaozhou Shi Dang’an Ju 1956d). He instructed his subordinates to conserve the emigrant graves as long as those graves did not obstruct agricultural activities. In 1956, three prominent political figures with diasporic ties, Yi Meihou, Fang Junzhuang, and Huang Changshui proposed to the Renmin Daibiao Dahui (National People’s Congress) that the key to advancing the United Front among overseas Chinese was to enforce a ban on the “arbitrary demolishment, relocation and destruction of their ancestral graves” in Chaoshan and Meizhou. This proposal should be read against the widely reported incidents of the desecration of emigrant graves. Even Toshan (Taishan) County, a well-established Cantonese qiaoxiang region in the Pearl River Delta, succumbed to the collectivization effort and lost many emigrant graves (Anonymous 1958).

Variations on the basic pattern of preferential treatment of overseas Chinese signaled policy incoherence. Some village cadres detested privileges given to overseas Chinese and targeted their ancestral graves (Chan 2018, 155–56). A native of Fuyang (Floating Ocean) in Chaoshan, Wang Xiguang, made a fortune in the Federation of Malay and returned home to repair his father’s grave. After the repair was done, Wang entertained relatives and gave them valuable gifts and photos as souvenirs. A few days later, he was shocked to see the grave badly damaged by villagers he did not entertain. Wang immediately petitioned the Shantou municipal officials to telegram the Chao’an County authorities to intervene. The uncooperative cadres in Fuyang were determined to expropriate resources from huaqiao and ignored the complaint, thereby emboldening the intruders to destroy the whole grave. Wang refused to go quietly and petitioned the Shantou authorities for help. His appeal was significant as he tried to hold the municipal officials accountable when rural cadres failed to deliver. Despite his ability to access bureaucratic resources, Wang learned quickly that resistance was futile. Out of fear of his relatives’ marginalized status, he requested an exit permit for his aging mother to go to Malaysia. The destruction of his father’s grave triggered panic and prompted him to doubt the State’s preferential treatment of huaqiao households. Therefore, “the idea of home being portable” was “a shifting, groundless, constructed notion” that drove Wang to find a new resting place in Singapore (Sinn 2013, 306).

The aggressive campaign to clear graves jeopardized the symbolic meaning of ancestral graves for huaqiao. Ideally, the cosmological and kinship ties encouraged huaqiao to remit their meager earnings from back-breaking labor and constant savings to maintain the home graves. After all, a decent burial of the dead and proper management of their graves would fulfill one’s obligation to the deceased, ensuring the promise of a good afterlife. As with other Chinese, huaqiao revered their family graves as sacred and worried that without proper burial arrangements, the ancestral spirits would haunt them and cause misfortune. Thus, they treated the massive destruction of family graves with disgust and felt skeptical of the new People’s Republic to protect ethnic Chinese abroad. In this perspective, the temporary ban on the “arbitrary demolishment, relocation and destruction” of ancestral graves was a damage-control measure to alleviate huaqiao fear. This policy urged rural authorities to conserve the emigrant gravesites when the structures did not obstruct agricultural production (Diyijie Quanguo Renmin Daibiao Dahui Disanci Huiyi Minshuchu 1956, 1:206–7). By putting forward the proposal to the National People’s Congress, Yi, Huang, and Fang raised awareness in the political center. Subsequently, the Guangdong provincial and county authorities issued directives to protect the family graves of huaqiao (Anonymous 1956b, 1956c, 1956a). In 1958, Chenghai County built multiple huaqiao cemeteries to cater to the needs of huaqiao and guiqiao (Anonymous 1962a). A “grave repair” association organized by village cadres was founded to welcome overseas visitors, but the well-intentioned initiative imposed heavy commission fees on huaqiao (Li 1956; Anonymous 1957).

Even in its local manifestation, the preferential treatment of huaqiao was calculative and situational, reflecting Beijing’s awareness of the urgency of this problem in coastal provinces. According to Stephen Fitzgerald (1969, 116), “In mid-1955, the Guangdong provincial authorities issued a directive on the protection of Overseas Chinese ancestral graves to avoid negative Chinese media coverage of the desecration of Overseas Chinese graves in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia.” It was in the sphere of funeral practices that the State made an exception for huaqiao with diasporic ties in Hong Kong, Macau, and Southeast Asia (Guangzhou Difangzhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui 2000, 597). On August 11, 1957, officials permitted the production and use of ritual materials by huaqiao for marriages, funerals, birthday celebrations, home construction, and grave repairs. To ensure a steady inflow of remittances, they raised the monthly grain supplies to 22.5 kilograms for huaqiao compared with ten kilograms for urban residents (Chaozhou Shi Dang’an Ju 1957). When hosting overseas visitors, huaqiao families would receive a daily supply of half a kilo of rice per person for three consecutive days. Afterward, visitors could apply for extra food coupons (Chaozhou Difangzhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui 1995, 797–801). In 1966, visitors from Macau were permitted to bring ritual products and pork offerings when coming to sweep the ancestral graves. These privileges, unavailable to the general population, were a relief to huaqiao. The preferential treatment was based on the political consideration that “the returning diaspora, given its social backwardness and strategic distinctiveness, had to be brought into the nation differently and far more gradually than others” (Chan 2018, 149). The cadres, who had demolished numerous ancestral graves to implement the land reform measures, were now part of a temporary solution to secure huaqiao goodwill. However, the Cultural Revolution changed the situation from 1967 to 1970. Officials banned visitors from bringing ritual products and foreign currencies and instructed them to see the propaganda shows staged near the gravesites (Mao 2018).

The correspondence between overseas Chinese and their relatives, known as qiaopi, reveals a continuous flow of remittances to support ancestral worship (Chaoshan Lishi Wenhua Yanjiu Zhongxin 2007, 2012). People in Hougou and Dawu avoided mentioning sensitive subjects to please the postal censors, but bad news still reached the Chinese press in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Southeast Asia. The Chao’an County officials acknowledged that many older huaqiao detested the coercive grave removals and lost hope of being buried in their ancestral homes. In March 1956, the provincial government instructed its county officials to alleviate such fear (Chaozhou Shi Dang’an Ju 1956a). The scale of grave demolitions in the 1950s was unprecedented, and the considerable numbers of bone boxes and coffins of deceased huaqiao from Southeast Asia were stranded in Hong Kong, prompting the call to find new burial space locally (Anonymous 1962b; Sinn 2013, 293). In this troublesome environment, Nanyang Chinese experienced what Hong Liu and Geoffrey Wade describe as an attitudinal change from a sojourning mentality to a territorial identification with the independent states (H. Liu and Wade 1999). Whereas Chaoshan-born huaqiao remitted money to support relatives, local-born children of huaqiao lacked such sentimental ties and chose Chinese-run cemeteries in Southeast Asia for their deceased elders (Lebra 2009, 113; C.-C. Choi 2020, 167).

Conclusion

As in other parts of China, the Maoist era witnessed a drastic restructuring of society in Chaoshan that changed the connection of huaqiao to their native homelands. When the State adopted a utilitarian approach to land use in the 1950s, it gave a green light to rural officials to flatten scattered graves for collectivization. From the space-saving perspective, the State freed more land resources for accelerated collectivization. These coercive measures transformed Chaoshan from an elastic emigrant society into a state-centric agrarian entity. By prohibiting the establishment or restoration of lineage cemeteries and by replacing ground burials with cremation, the State eliminated the sentimental and sacrificial links that connected huaqiao with their ancestral land (Guowuyuan Fazhi Bangongshi 2016, 419). In areas with a migration history to Southeast Asia, elderly huaqiao were shocked by the news. The panic prompted many huaqiao to settle in the hosting society, changing their perception of ancestral “roots” and permanent “home” after death (Sinn 2013, 294).

Since the 1980s, the gradual penetration of transnational Chinese influences into Chaoshan has reshaped the socio-political and cultural mechanisms of state control, enabling huaqiao to reconnect with their homelands. As time progresses, the mode of expressing emotional ties to ancestors has changed. Tangible graves have been replaced by public cemeteries and modern columbaria, and huaqiao send remittances home to pay for the upkeep of newly restored graves. The new graves serve as identity markers for huaqiao, symbolizing emotional ties to their ancestral homes and reinforcing kinship bonds across boundaries. Beyond their cultural and familial significance, they offer a sense of continuity in the face of disruptions caused by the grave relocation campaign of the 1950s. Through transnational support from Southeast Asia, many huaqiao have leveraged resources to preserve burial customs within their communities and adjusted to the new funeral culture, willingly or unwillingly, by aligning their affective attachment with the State’s modernizing agenda. These adaptive strategies highlight the resolve of Chaoshan huaqiao to navigate the interplay of state intervention and transnational influences at the grassroots level.

A single-surname settlement is a village where residents share the same surname and trace their descent to a common ancestor.

A single-lineage community is composed of members of the same lineage who trace their common descent to more than five generations. It sets aside extensive ancestral estates to support regular ritual observances and grave conservation.

The pingfen (grave-flattening) campaign of the 1950s was an official policy aimed at clearing scattered graves and reclaiming burial sites for agricultural collectivization. The campaign was followed by the promotion of cremation as part of a broader effort to maximize land use and eliminate what the State perceived as “feudal superstitions.”

Interview with Participant D, June 15, 2023, conducted by Hui Wang in Hougou.

Joseph Tse-Hei Lee recalls this story shared by his late father, a native of Guxi (Ancient Stream).

Interview with Participant A, February 25, 2023, conducted by Hui Wang in Hougou. Participant A became a successful entrepreneur during the Reform era and donated generously to support public health and fitness programs in Hougou. For details, see Hui Wang H. (2022).

Interview with Participant B, February 26, 2023, conducted by Hui Wang in Dawu.

Interview with Participant C, July 10, 2014, conducted by Hui Wang in Hougou.

_and_dawu_(big_wu__blue_point)_in_chaoshan_(coll.jpeg)

_and_dawu_(big_wu__blue_point)_in_chaoshan_(coll.jpeg)